| Home -> James H. Barry Press -> The Great Diamond Hoax - Chapter XXV | |||

|

Chapter XXV.

Inspired by Desire to Expose Emma Mine Swindle Author Begins Publication of Financial Journal. Ralston Reports Discovery of Immense Diamond Field and Declares His Find is Worth $50,000,000. Many times I had learned to have a deep respect for printer's ink. I had seen it make history, change fortune, influence the thought of great bodies of people, prove a mighty instrument for good or ill. Without the least desire to be disrespectful, to the present, I have a strong impression that the journalism of fifty years ago had a wider dominion over the minds of its readers than the modern school. I cannot say that this was always for the best. Men had a blind devotion to their pet newspapers that amounted to something very much akin to bigotry. Such newspapers were the final authority on everything from religion to politics, and everyone who questioned their opinions, politics or statements had a fair prospect for a fight. Thus when an editor fell into some grievous error he was certain to pull nearly all of his subscribers into the same abyss. So I realized that to have any influence in my new place of business, to attack the power of Baron Grant, now bitterly antagonistic in every way, and to offset the Emma mine fraud, I must have a personal organ. For this purpose, I established a financial weekly paper known as the London Stock Exchange Review. It was issued, for apparent reasons, ostensibly by a brokerage firm, but it was an open secret that the publication was mine. I engaged an able editor-in-chief, and directed him to employ the best financial writers in England, giving each his proper department, such as railroad securities, industrial, mining shares, foreign and domestic loans and the like. I retained a page for which I furnished material hot enough to burn holes in an asbestos blanket. The page was devoted to the Emma mine and Baron Grant. The Stock Exchange Review was a breezy, well-written sheet, full of valuable information to investors, put together in an attractive, readable form. I had set aside £6,000 to pay the losses of the venture. Much to my surprise and pleasure, it proved a moneymaker from the start. The style was such a departure from the ordinary dry-as-dust publications of its kind that it made a hit on the street with the first issue. The price was a shilling, but often big premiums were offered when it came out with an extra seasoning of tabasco. I had reason to know that it tickled the hide of Baron Grant unpleasantly. It managed to hit on a number of raw spots in his past career, and in particular interfered with the Emma mine proceedings. While I spoke as a private person, my charges might be disregarded, but when a publication, reasonably responsible in damages and absolutely responsible in a criminal charge, made a downright allegation of fraud, that was quite another thing. The libel laws of England were then, as now, airtight. It was not a jocular affair to call anyone a thief in print, and those who did not seek redress had to suffer under the suspicion, just or unjust, that the accusation was substantially true. The Emma mine was brought out in two sections, for promoting each of which Baron Grant received a commission of £100,000. When the first section was issued it almost took a squad of policemen to keep back the crowd of investors. The second appeared just after the Stock Exchange Review began to hammer. While the stock was taken, the promotion staggered and was never quite itself again. One thing it prevented absolutely - the declaring of a great dividend - on air - which would have sent the stock skyward like a rocket. The managers had determined on this piece of rascality, but doubtless fearing that I had certain knowledge of the fact that not a dollar's worth of precious metal had been produced, this particular piece of villainy was reluctantly abandoned. In the meanwhile, I began to have suspicions of the integrity of Samson, the financial editor of the London Times. I could not think he was ignorant of what was going on in the Emma mine deal. His attitude toward several shady promotions looked, to say the least, queer. In the days of our intimacy Baron Grant had more than once broadly intimated that he possessed some kind of mysterious hold on Samson. Whenever I suggested Samson's name as a possible factor in our enterprises he always said smilingly, "He'll be all right." For some time previous I had a passionate yearning to get a look at the financial writer's bank account. I communicated this desire to Alfred Rubery one day, just as the expression of a wish. Rubery, who knew all the ropes and all the ins and outs of London, pondered a few moments and said he thought it might be arranged. I was overjoyed at this intimation, but could not exactly see how, though my friend, had an odd way of doing things seemingly impossible, in an everyday fashion. He was of an impulsive character, a most loyal, trusty and affectionate friend, yet nothing on earth could ever jar him out of his marvelous British self-possession. I remember one occasion in San Francisco in the old Chapman days, when Rubery and I were present at a certain meeting, when a wholesale slaughter was on the point of taking place. Just at the crisis I happened to glance at Rubery. He was sitting in his chair with a bored, blasé expression on his face, as if tragedies were so commonplace in his life that they lacked interest and were positively wearisome. This incident has nothing to do with the story further than to illustrate the singular character of the man - a mixture of dash and enthusiasm under strong control. At that time money could accomplish almost anything in England. A few evenings after our conversation, Mr. Rubery waited on me at my rooms, accompanied by a dapper looking person, whom he introduced as an official of the Bank of England, who had access to the accounts kept there by Mr. Samson and who was willing for a reasonable compensation to give me all the information concerning the same I might desire. To which pleasing presentation the official of the Bank of England gravely bowed. Some conversation followed as to the terms and conditions. The official wanted all that was coming, but evidently did not wish to scare off a good customer by an extravagant price. At last he got down to a cold cash proposition. Would I consider, under all the circumstances, £500 excessive for so delicate a service? A bargain was struck readily enough. Much better terms would have been cheerfully granted. The contracting party underestimated his hand. Through this person I secured an accurate statement of Mr. Samson's transactions. I even was shown checks and cross checks, which I photographed for future use. These proved beyond all question that Mr. Samson was a beneficiary of the Emma mine promotion, that he had profited largely by other deals, and, in short, was faithless to the trust of his employer, and trading on that trust. Here loomed up the outlines of a great dramatic situation, the unmasking of a conspiracy, the righting of many wrongs, by which the villain of the play would be confounded and the innocent come to their own. Only the details needed rounding out to clear the atmosphere and let the curtain fall. I was deeply engaged in these great affairs when I received a cable from Mr. Ralston. It was, in fact, a letter. At the cable rates then in force, it cost over $1,100. When I read it I felt assured that my old friend had gone mad. It told me of a vast diamond field just discovered in a remote section of the United States. His description of it made Sinbad, the Sailor, look like a novice. He said that diamonds of incalculable value could be gathered in limitless quantities at nominal expense; that they could be picked up on the ant hills; that at a low estimate it was a $50,000,000 proposition; that he and George D. Roberts, a well-known mining man, were in practical control. Finally he almost demanded that I should drop everything, take the next steamer and act as general manager. The extravagance of his language alone seemed to me to indicate that he was laboring under some strange delusion. However, diamonds or no diamonds, I was in no position to stir. I cabled him briefly that my business in London was of too vital importance to admit of considering other engagements. But that did not satisfy Ralston at all. Cable followed cable, urging, imploring, beseeching me to come on, which were invariably answered in the same way. Still I was worried and perplexed. Rumors began to float into London about the discovery of a vast diamond field in the American continent, controlled by the great California banker, W. C. Ralston. Many financiers called on me for information, knowing our relations. Among others, Baron Rothschild sought an interview. He asked me what I knew about the diamond fields, and I frankly showed him Mr. Ralston's cables. He read them with interest and asked me what I thought myself. I told him that while I had great confidence in Mr. Ralston, I thought he must have been imposed upon in some way, and that in due season the bubble would burst. Baron Rothschild mused a moment. "Do not be so sure of that," he said. "America is a very large country. It has furnished the world with many surprises already. Perhaps it may have others in store. At any rate, if you find cause to change your opinion, kindly let me know." This remark, made by perhaps the keenest financier in the world, was enough to set any one thinking hard. My position was one of extreme difficulty. The most important engagements of my life demanded my presence in London. Of course I knew that in my absence everything must mark time. But little by little the impression began to grow on me that Mr. Ralston had actually captured a fifty million dollar financial circus and that I was badly needed as ringmaster. His cables did not deal in hopes, but absolute certainties - assured facts. The diamonds were not a dream - a small fortune of them taken from an insignificant trench were already in his possession. Finally came a cable begging me to go to California, if only for the briefest stay, say sixty or ninety days. I had engaged offices in London for seven years. I could see ahead a vast future of activity and success, and I did not want my selected career broken into by outside distractions, however brief. But I commenced to take the appeals of Mr. Ralston more seriously. Casual expressions of opinion such as the one noted by Baron Rothschild began to stir up my imagination a bit. Could it really be true that there was a place where diamonds could be picked up on ant hills? It was very easy to find out the truth, and if the truth happened to correspond with Mr. Ralston's statements, then everything else in the world in the way of business or enterprise seemed commonplace and cheap. I laid the matter before Alfred Rubery, who usually had a level head. He was surprised at my reluctance. "You have your men safely trapped here," he said. "There is no possibility of escape, and whether they enjoy for a brief time a sense of fancied freedom, matters not in the least. Make up your mind to go to California and find out what all this cable correspondence means. Personally, I am bored to death, just pining for a little bit of excitement. I will go along with you and we will stir up things again in the Far West." Pressure came on every side. I must have had a forewarning of disaster to have hesitated so long, but finally I gave way to forces that seemed like fate. I cabled Ralston that I would be at his service for a brief period, but that the proceedings must be short and sweet. Also I made a hurried arrangement of my affairs in London, thinking to take up the thread again in three months at most. Rubery was rejoiced at my decision, and prepared to go along. We turned our backs on London, stayed not on the order of our going when we reached New York, and as fast as steamships and railroads would carry us, arrived in San Francisco some time during the month of May, 1872, prepared to uncover the greatest diamond field in the world or return whence we came with equal expedition. |

|||

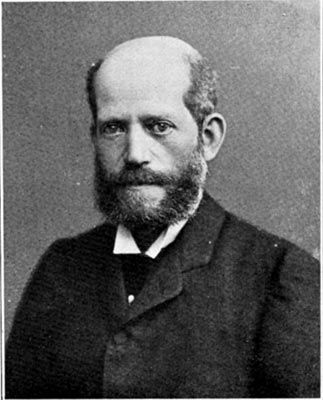

Barron Rothschild Head of the great financial institution in England in 1872. |

|||