| Home -> Paul Elder -> Palace of Fine Arts and Lagoon - Text | |||

|

|||

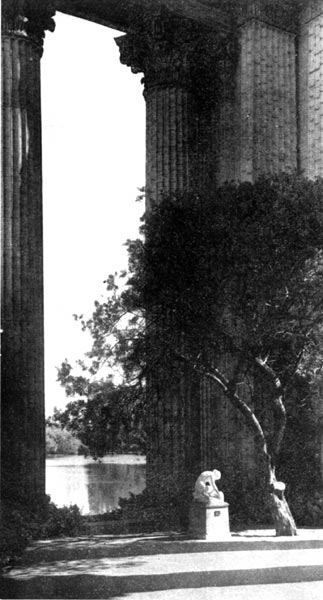

The Muse Finding the Head of Orpheus The Marble by Edward Berge as placed under the Acacia Tree in the Peristyle, Palace of Fine Arts |

|||

|

A little time, a little space away

Noise and tumultuous color and the world at play! Here 'neath the drooping branch, the low-bent marble Muse; On either hand the Master-builder's columns tall; The little lake caressed by cloud and sky; The quiet of the dying daylight over all! Man praises man's accomplishment with brazen throat; Beauty alone can charm with one low note. John E. D. Trask |

|||

|

Palace of Fine Arts and Lagoon

Panama-Pacific International Exposition, 1915 By Bernard R. Maybeck With an Introduction By Frank Morton Todd |

|||

|

|||

|

Paul Elder and Company

Publisher San Francisco Copyright 1915 By Paul Elder and Company San Francisco I am deeply grateful to the two men who made possible the Fine Arts Palace, as it is: Willis Polk and Harris D. H. Connick |

|||

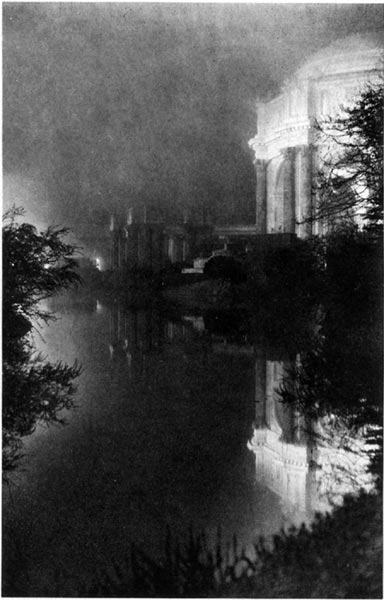

Palace of Fine Arts and Lagoon - A Foggy Night |

|||

| Contents Lines on "The Muse Finding the Head of Orpheus" by John E. D. Trask, Director of the Department of Fine Arts, Panama-Pacific International Exposition. (Tissue Facing Frontispiece.) Introduction. By Frank Morton Todd Palace of Fine Arts and Lagoon. By Bernard R. Maybeck, Architect of the Palace of Fine Arts, Panama-Pacific International Exposition Illustrations The Muse Finding the Head of Orpheus. The Marble by Edward Berge as placed under the Acacia Tree in the Peristyle, Palace of Fine Arts. (Frontispiece.) The Palace of Fine Arts and Lagoon, A Foggy Night. William Hood, photo Introduction After the little, breathless shock that follows the first vision of perfect loveliness, half the world and his wife looking across the Fine Arts Lagoon in San Francisco, ask: "Who did it? Where did he get his inspiration? Why have we had to come here to see the most divinely beautiful building ever reared in America?" The following pages tell. They are the frank, direct answer of the man who had that glory and grandeur in his brain, and has gone about among us all these years a simple good friend and neighbor. And his neighbors, by the way, knew it was there. Naively as a little child Maybeck explains, and thereby reveals unconsciously his marvelous power of over-leaping time and space and translating himself mentally into another age - any age you like, apparently. There seems to be nothing difficult about it to him. It is just his method of attacking the problem; and in feeling and understanding, he steps back twenty centuries as easily as you or I would cross a room. He built us a club-house in our hometown of Berkeley. "Now," he said, "this is an organization of neighbors who like one another and wish to have a sort of common home for the hours of their meeting together. It must FEEL that way." It does. With naked timbers stayed, braced and tied together in the handsomest and most powerful structural forms, it is as intimate and stable and homey as an old stump. That club holds its membership - draws the old members back again and again, will not let them stray, for it is a sure shelter o' stormy nights, and a great simple hollow of coolness other times. Its open timbering is Californian. He built it for Californians. Called upon to build a church for a new sect, instead of consulting books on architecture he asked about their beliefs, and was given testimony of such strong and measureless confidence in their creed that he said it seemed a faith like that had not been in the world since Christ was in the flesh. Then his problem, to him, was to design a church that would fit and satisfy the joyous, holy feelings of an early Christian; perhaps an apostle, or a holy martyr. The result is a gilded, painted, grey-and-golden, blue-and-silver glory of Byzantine and Gothic elements that makes the heart sing to look at it. There is nothing mysterious about the process. It is the democratic habit of putting yourself in the other fellow's place; according to Christ, and Confucius, and all the other ethical teachers that have been worth anything. And yet, how hard to do! And how rare! In the Palace of Fine Arts and the lagoon that is part of the composition, he has accomplished a double self-translation. He has gone back to the classic age for his elementary forms, standing where a young Greek would have stood; and he has come forward again to the present, putting his building on the edge of a tarn and giving it the melancholy of old ruins by a landscape treatment intended to throw it into the background. It is across water from the Avenue, partly veiled in trees; remote, mystical, unspeakable, neither to be touched nor told. Of a misty evening, when the pool first begins to reflect the delicate silver film the searchlights put on the fluted columns, its frosty and unattainable perfection is as moving as a glimpse of the Infinite. If we only knew it was well based, and built of hard, well-jointed stone, we should know it had added importantly to the world's imperishable beauty. If it could stand there a hundred years while swamp growth swathed its piers and plinths, while willows and acacias choked its portals, grasses dug into its urns and ivy over-ran its cornices and dimmed its lines, posterity would revere it above all other physical possessions. It is on its way to the land of dreams and memories. But while it stands it is Karnak, and ghosts of old Rome, with the passionate spiritual ardors of the Middle Ages bursting through the classic chrysalis. For, in spirit, Maybeck is a medieval monk. In his scholastic idealism and detachment lies the secret of the Fine Arts Palace. - Frank Morton Todd. Palace of Fine Arts and Lagoon On desperate seas long wont to roam, In discussing a subject such as that of making plans for a World's Fair, it is necessary to assume that the hearers admit there are mental processes not to be expressed in language. The first example that comes to our mind is the process of understanding music. Stone and wood construction proper bears the same relation to architecture that the piano, for instance, does to the music played upon it. Music and architecture are vehicles of expression for phases of our human experience. Omitting construction, we will discuss only the architecture as a conveyor of ideas and sentiments. The combinations and arrangements of the buildings and gardens at the Fair were planned according to the principles discovered by the French architects. Besides other phases, the fundamental idea was that the picture presented by the ground plan of a group of buildings and their surroundings should be agreeable to the eye, and therefore in the development of the plan it is treated as though it were an ornament, without regard to the fact that it represents buildings. If the plan of the Panama-Pacific International Exposition group of main buildings were reduced in scale to the size of a golden brooch and the courts and buildings were made in Venetian cloisonne jewelry, that brooch thus made would pass as the regular thing in jewelry without causing the suspicion that it represented a plan for a World's Fair. To be an ornament the plan must have a sense of direction, and in the Panama-Pacific International Exposition it has a top and bottom, of which the Machinery Hall would be the bottom and the Fine Arts would be the top, with relation to the geometric center of gravity. Now, besides the physically ornamental, there is a spiritual significance in the plan. There is a succession of impressions produced as one walks through the different parts of the grounds that play on the feelings and the mind, each part having its own peculiar influence. Along the main axis, for example, the Machinery Hall and neighborhood suggest a mixture of the classic and romantic as you understand the terms in literature. The Court of Abundance, better called the Court of Ages, suggests the medieval with all its rising power of idealism in conflict with the physical. The Court of the Universe suggests Rome inhabited by some unknown placid people. The Court of the Four Seasons suggests grace, beauty and peace in the land where the souls of philosophers and poets dwell in continued satisfaction. The Fine Arts Palace suggests the romantic, of the period after the classic Renaissance. Someone familiar with the philosophy of art will no doubt wish to challenge this classification of the various courts, but I believe it will be admitted that some such classification can be made for one class of mind, and other classifications for other minds. These terms, "romantic," "classic," etc., are usually covered by the word atmosphere - the physical forms reflect a mental condition. For instance, when the Director of the Division of Fine Arts explained what he felt was necessary for a Fine Arts Palace, he said that he did not want the visitors to come directly from a noisy boulevard into collections of pictures, but on the contrary he wanted everybody to pass through a gradual transition from the exciting influences of the Fair to the quiet serenity of the galleries. Mr. Trask not only wanted the mind of the visitor to be in a tranquil mood but he worried lest the high coloring on the outside of the building would dull the eye to the delicate shades of some of the light-toned pictures. In the same way Mr. Trask wanted all the smaller details to be harmonious with the rest of the architecture. He wanted the pedestals, the water pools, the rubbish cans, the color of the walls, all to fit in. All of these details collectively make an atmosphere. Let us analyze the Fine Arts Palace and lake, not from the physical but rather from a pyschological point of view with reference to the effect of architectural forms on the mind and feelings, and discuss the various elements which influenced the composition of the architecture and landscape. The first question to settle is, what character should an exhibition building of paintings have; and the second question is, by what process may we find the elements of architectural forms that will give the feeling that corresponds to that of the exhibition of paintings. The first is fixed; the second must waver back and forth until the nature of the building reflects that of the exhibit. The first question depends upon the character of the paintings to be housed, and the second depends upon finding such forms as will portray the character of the paintings, and, using that character for your theme, weaving it into all the parts of your composition as though you were composing a musical symphony. We can perhaps get a little clearer idea of the foregoing remarks through discussion of an art gallery composed of five-dollar Broadway hand-made paintings, the gold frames of which cost more than the labor of painting the picture. These pictures could be fitly housed in a building called "Palatial Picture Palace," which to be in harmony should remind you of an overdone ice-cream parlor or candy store, with many steam orchestrions playing various tunes just far enough apart so that they audibly compete with each other. The magnificent gardens should be all hand-made artificial plants and artificial waterfalls. Such an art palace might be deemed to have a Broadway atmosphere and, of its kind, a harmony of discords. Each form that is used must be of the same feeling as the Broadway picture. The Fine Arts exhibition is made up of units representing the best efforts of the artists, the beginning of which started years ago. The work did not begin, as some people imagine, when the artist made his first lines in charcoal on his canvas, and did not terminate in a few hours and then sell for fancy prices. Indeed, some of an artist's dreams are put into execution many years afterward. In every good painting there is a quality which makes you feel that years of experience have preceded it. The artist began his work a long time ago in a nebulous haze of whys, and it is usually a long experience before his paintings are nearly as good as a photograph, and oftener a great deal of hard work and disappointment must come before he suspects that it is not the object nor the likeness to the object that he is working for, but a portrayal of the life that is behind the visible. Here he comes face to face with the real things of this life; no assistance can be given him; he cannot hire a boy in gold buttons fashionably to open the door to the Muse, nor a clerk nor an accountant to do the drudgery. He is alone before his problem and drifts away from superficial portrayals. After this he strives to find the spiritual meaning of things and to transmit that secret to the layman. Sometimes the artist has not received his message clearly enough and the layman fails to understand. So each picture is a message which the artist has deciphered after many years of work, and artist John Doe always tells the same message, whether it be the lady in pink or the wave crest, but it is a different message from the other pictures painted by Richard Roe. A picture by Whistler is always a Whistler; Mathews' paintings are always Mathews. From the paintings of any historic period one gets a reflection of that age. Therefore in a collection of ancients and moderns such as the Fine Arts exhibit you will find many atmospheres, which leave as a sum total of impressions a single one; just as of the instruments of an orchestra, the violins play one set of notes, the flutes another, the 'cellos another, altogether myriads of sounds, which may be recorded on a phonographic disc in one set of vibrations, producing the sum total of sounds. The sum total of impressions of an art exhibit I got while visiting one of the art galleries in Munich. With others we dragged ourselves from gallery to gallery seeing Madonnas and Christs crucified, also a picture which portrayed a Polish princess sitting on a throne in a courtyard in midwinter, who in a mad fit ordered freezing water to be thrown over nude maidens, amid snow and icicles. Some of the maidens in the foreground were dying and others lay dead, ghastly and frozen. And farther on we saw Böcklin's "Isle of the Dead," and on we wandered. We dragged ourselves along until we came to the broad marble stairs leading out into sunshine once more, but we sat down for a moment's rest before leaving. All at once our eyes fell on the marble bust of a five-year-old boy cleverly portraying a little mischief, and underneath the bust were the words, "Dear God, make me pious," - and we smiled. We watched the weary faces come out of the galleries and one by one when their eyes saw the bust, the drawn expression relaxed; some smiled, some laughed, but all seemed to be brought back to a happy life, and we realized right there that an art gallery was a sad and serious matter. Some years ago there appeared a story by David Graham Phillips, and by some happy accident the atmosphere of each part or chapter of the story was portrayed in a frontispiece by an artist named Wenzel. In this frontispiece Mr. Wenzel depicted the sum total of the general impression of what was to follow so successfully that I could anticipate the contents, although the frontispiece might have been only a Diana and her hunting dogs, and Diana had nothing to do with the story. Now what Mr. Trask wanted was a frontispiece to his art collection, which would anticipate the general impression as a whole. And if among the many pieces of sculpture I were to choose one piece that came nearest to being a frontispiece of the general impression of the exhibition of painting, I would choose the white marble Muse finding the head of Orpheus, which was made by Berge, and now stands under the acacia tree at the south entrance. Summing up my general impression, I find that the keynote of a Fine Arts Palace should be that of sadness modified by the feeling that beauty has a soothing influence. Now follows the second part, the architect's part. To make a Fine Arts composition that will fit this modified melancholy, we must use those forms in architecture and gardening that will affect the emotions in such a way as to produce on the individual the same modified sadness as the galleries do. This process is similar to that of matching the color of ribbons. You pick up a blue ribbon, hold it alongside the sample in your hand, and at a glance you know it matches or it does not. You do the same with architecture; you examine a historic form and see whether the effect it produced on your mind matches the feeling you are trying to portray - a modified sadness or a sentiment in a minor key. An old Roman ruin, away from civilization, which two thousand years before was the center of action and full of life, and now is partly overgrown with bushes and trees - such ruins give the mind a sense of sadness. The Renaissance French artists portrayed the same sensation in the fountains in the forests of Versailles, made up half of shrubbery, half of marble - imitation ruins, Dianas, gods and goddesses, waterfalls. These today have a spirit of sadness because the trees and bushes are old; nature outgrew the gardeners' stiffening care. Great examples of melancholy in architecture and gardening may be seen in the engravings of Piranesi, who lived a century ago, and whose remarkable work conveys the sad, minor note of old Roman ruins covered with bushes and trees. There seems to be no other works of the builder, neither Gothic, nor Moorish, nor Egyptian, that give us just this note of vanished grandeur. "They say the lion and the lizard keep Overdone in sadness for an art gallery frontispiece would be the "Isle of the Dead" - a dark picture of an island of tall black trees enclosing a white marble columbarium; in the foreground a boat carrying the dead across. The islands of Clear Lakes, California, where the trees and bushes seem to rise out of the water, make the same impression of sadness as Böcklin's picture, but in a lesser degree. But the feeling given by the Clear Lake islands is similar to the sentiment expressed in the statue of the Muse finding the head of Orpheus - its beauty tempers the sadness of it. As an example of what is meant by matching impressions: suppose you were to put a Greek temple in the middle of a small mountain lake surrounded by dark, deep, rocky cliffs, with the white foam dashing over the marble temple floor - you would have a sense of mysterious fear and even terror, as of something uncanny. If the same temple, pure and beautiful in lines and color, were placed on the face of a placid lake, surrounded by high trees and lit up by a glorious full moon, you would recall the days when your mother pressed you to her bosom and your final sob was hushed by a protecting spirit hovering over you, warm and large. You have there the point of transition from sadness to content, which comes pretty near to the total impression of the Fine Arts Palace and lake. By the process of finding forms of architecture and gardening for the general composition of the Fine Arts Palace and lake that will best convey the same impression to the heart and mind as those impressions made by the works of art inside, the mind of the visitor to the gallery is prepared as he enters for what he is to see, and as he comes away his senses gradually are led back to the commonplaces of human activity; and the horns of automobiles, the cries of the popcorn venders, will not grate upon his ears as they would if he were plumped out directly into the hustle and bustle. From the standpoint of the composition of the whole scheme, or symphony, of the main group of buildings of the Fair, this lower key of the Fine Arts Palace helps to give a finish; and beyond, the Sunday-like appearance of the State pavilions also helps let the visitor down gently from the strain of the galleries. This paper was written to point out one of the phases of the Fair, in the hope that people will realize that such a group is not a conglomeration of soulless buildings dolled up in holiday attire like the palatial palace of Broadway pictures, but that in the Panama-Pacific International Exposition is expressed the life of the people of California. It has its geographic stamp just as the architecture of Tibet has its geographic reason for being. This same group could not have happened in Boston or in India. When the people of California visit the grounds they should think of the fact that the Fair is an expression of future California cities, and although the columns of the courts will not appear in the office buildings on Market street, nor the triumphal arches appear in the residence part of their towns, the future city of California will have the same general feeling; because it will be a California city. Here ends Palace of Fine Arts and Lagoon, Written by Bernard R. Maybeck, with an Introduction by Frank Morton Todd; and the Frontispiece is from the Marble by Edward Berge accompanied with a verse by John E. D. Trask. Published by Paul Elder and Company, and printed under the Typegraphical Direction of H. A. Funke at their Tomoye Press in San Francisco during the month of September, Nineteen Hundred Fifteen. |

|||

|

|

|||