| Home -> Other California History Books -> The Spirit of 1906 - The Morning of April 18th | |||

|

|||

|

The Morning of April 18th

|

|||

|

In common with the other half million citizens of San Francisco on that fateful morning, I was awakened from a sound sleep by a continuous and violent shaking and oscillation of my bed. I was bewildered, dazed, and only awakened fully when my wife suddenly screamed, "Earthquake!" It was a whopper, bringing with it a ghastly sensation of utter and absolute helplessness and an involuntary prayer that the vibrations might cease. Short as was the period of the earth's rocking, it seemed interminable, and the fear that the end would never come dominated the prayer and brought home with tremendous import the realization of our insignificance, of what mere atoms we become when turned on the wheel of destiny in the midst of such abnormal phenomena of nature's forces.

It was 5:15, broad daylight, and as I glanced at my watch those figures were indelibly fixed in my memory for the rest of my existence. The terror and horror which suddenly sprang like a beast of prey out of the gray dawn and grasped our heart strings, came unheralded from a day that otherwise promised all that should make life worth living. The night had been particularly warm and inviting. So vivid was this impression of the glory of the morning that I was possessed by a feeling of irony that such a beginning should herald the inception of so bitter a calamity. Fascinated, I stood gazing at a weathervane on the top of a house across the street. It swayed to and fro like the light branch of a tree in a heavy gale. I was jarred out of my inanition by a terrific shock. The house lurched and trembled and I felt that now was the end. It was afterward discovered that this crash and jar was caused by the falling of a heavy outside chimney, attached to the adjoining house. It had broken and struck our dwelling at about the first floor level and torn away about twenty feet of the sheathing, some of the studding and left a big hole through which the dust and sound poured in volumes, adding to the already almost unbearable confusion. The first natural impulse of a human being in an earthquake is to get out into the open, and as I and those who were with me were at that particular moment decidedly human in both mold and temperament, we dressed hastily and joined the group of excited neighbors gathered on the street. Pale faced, nervous and excited, we chattered like daws until the next happening intervened, which was the approach of a man on horseback who shouted as he "Revere-d" past us the startling news that numerous fires had started in various parts of the city, that the Spring Valley Water Company's feed main had been broken by the quake, that there was no water and that the city was doomed. This was the spur I needed. Fires and no water! It was a call to duty. The urge to get downtown and to the office of the "California" enveloped me to such an extent that my terror left me. Activity dominated all other sensations and I started for the office. As all street car lines and methods of transportation had ceased to operate it meant a hike of about two miles. My course was down Vallejo street to Van Ness avenue, thence over Pacific street to Montgomery. When I reached the top of the hill at Pacific street where it descends to the business section, a vision of tremendous destruction, like a painted picture, opened before my eyes. I saw fires on the water front, fires in the commercial district and also portentous columns of smoke hovering over the southern part of the city. Then like a blow in the face came the realization that all fire fighting facilities were nil owing to the lack of water. One short hour previous, San Francisco was sleeping peacefully in its prosperity, and now the sight was appalling. Devastation, far as the eye could see, was spelling death and destruction. My route was down Clay street from Montgomery to Sacramento. In that one block I counted twenty-one dead horses, killed by falling walls. They had belonged to the corps of men who bring in to the market with the dawn the city's supplies. When I reached the corner of California and Sansome streets (the California office being one block away on California and Battery) I found a rope stretched across from the Mutual Life Insurance Company Building to the site where the Alaska Commercial Company building now stands. All beyond was policed. A soldier of the regular army was on guard and no one was permitted to pass. Arguments and beseechments to get to the office were of no avail. The necessity and the emergency, however, stimulated my determination and aroused my ingenuity. Suddenly, I ducked under the rope and ran a Marathon which was not only a surprise to myself but also to the officers and the crowd who yelled after me. I am sure that in this one block my speed record for a flat run still stands unequaled. I reached the office and there found every intimation of a hasty departure on the part of the janitor. The front door of the building stood wide open. I rushed in, threw open my desk and hastily gathered an armful of what I deemed were the more important books and papers. Glancing around to see if there was any way of saving anything else I again received a jolt by noticing that the fire was coming down a light shaft from an adjoining building and through an open window into the rear office of the "California's" office. In fact, furniture was already burning in the president's room. This was no place for me. The only avenue of escape was the way I had come, since so rapid was the spread of the conflagration that north, south and east were already in flames. Upon reaching California street I rushed and headed west, and the instant I had passed, the entire four-story outer wall of the building located on the southwest corner of California and Battery streets (then known as the "Insurance Building"), fell with a roar, completely blocking the street over which I had just made my escape. Realizing that my safety was measured by a matter of seconds, I was for a moment unnerved. My legs trembled, my heart pounded and my breath came quickly, and only by a great exertion of will induced by the thought that it was time to do and not to hesitate, I made the effort and arrived safely at the rope from which I had started. I shook as if with the ague. Sweat and grime poured from me, but the shout that went up from the watching crowd and the many friendly hands that sought mine, gave me my second wind. I had already made up my mind that possibly the Liverpool and London and Globe Insurance Company and Colonel C. Mason Kinne would allow me to store within their vaults whatever salvage I had taken from my desk. My trust in their courtesy was justified. I was made welcome and the Colonel, in the name of the company, placed anything and everything that it had in the shape of assistance at my disposal. As we stood talking on the corner of California and Leidesdorff streets, a friend still living in San Francisco who had an office in the Liverpool and London and Globe Building suggested to me that I had better take an option on some of that company's vacant rooms. I spoke to Colonel Kinne, a verbal agreement to that effect was made, and I turned and smilingly remarked, little knowing what the future had in store, that the California Insurance Company would resume business in the Liverpool and London and Globe Building "tomorrow morning." I then stood and watched the firemen lower a suction pipe through a manhole in the middle of the street and pump sewerage on to the old Wells Fargo Building. It had about as much effect as a garden hose and the supply was soon exhausted. The firemen stood perfectly helpless, like soldiers without ammunition, in front of the enemy. The fire had now about everything east of Sansome street and in the absence of water it was only a question of one or two days at most when the entire city would be in ashes. This was not alone my impression but the same ghastly prospect impressed itself upon all those who were gathered in the vicinity. The minutes had ticked off until it was now about 8 a. m., when another violent shock occurred - a sort of postscript to the original 5:15 trembler. It was of short duration but while it lasted it was decidedly impressive. The crowd scattered and I with them, for we suddenly realized that another wall might fall with a crash and that we might be caught. This is the only reason I can assign for our agility in getting away, unless it might be that we simply followed the first and natural impulse of our overwrought nerves. |

|||

|

|||

|

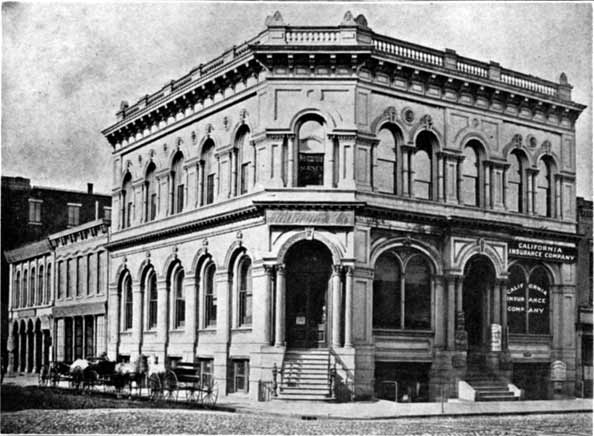

Office of Company, No. 230 California Street, San Francisco, From June 1905 to April 18, 1906.

|

|||