| Home -> Other Books -> Storied Walls of the Exposition -> Chapter 1 - General Plan | |||

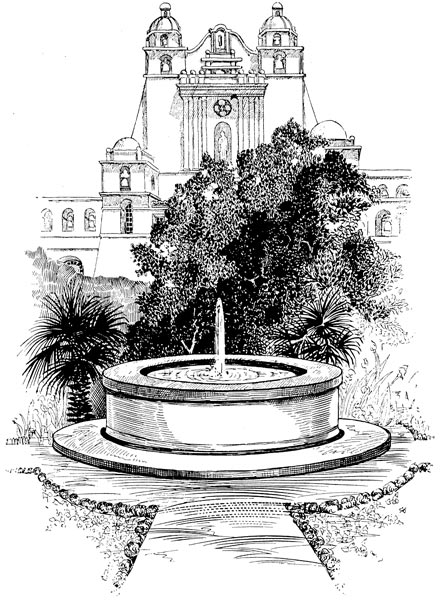

The Forbidden Garden Chapter I General Plan Lying as it does along the shores of the bay at the base of the city's hills, the Exposition seems a bit of the Orient set down beside this Western sea. Byzantine, Saracenic, Moresco - its softly rounded azure and bismuth domes, topped here and there by delicate floating balls, its tapering terraced towers, its red tiled roofs, all breathe a note of strange and distant lands. The cloistered courts; the separated buildings linked into a whole by pillared arcades; the masses of flat blank wall; the ornate portals; the delicate pointing fingers of the minarets - all are notes of Spain. In the colors too is seen the spirit of the Eastern land. The blues, the browns, the rose, the gray, the soft dull tint of travertine, the splendid bursts of gold, have nothing in common with this new land. They are all of Spain and of the East. In a marvelous unity with this atmosphere, the architects have introduced touches of decoration from other times and other lands. The arches of the Court of the Universe are Roman; their ornamentation largely Saracenic; the lines of stately columns are Greek; the banding friezes Greek too; and that sense of the open out-of-doors is Greek, for in the early days of their glory the Greeks prayed to their gods under the open sky and fenced their places of worship with the slender trunks of the trees. Machinery Palace is Roman in its impressive leaping arches and its heavy cornices, but the note of Spain is in its tiled roof and the treatment of the architectural decoration. The doorways of this mighty palace are superbly Roman. In the group of palaces all the doorways have the ornate note of Spain, varying from the typically Spanish door leading into the Palace of Varied Industries through the colder and more classic doorways of the other palaces to the Marina where, in the entrances on the northern front, is the elaborate plateresque, the silversmith filigree work of that first period in Spanish Renaissance architecture - the days of Ferdinand and Isabella and to Philip II. To the west the Palace of Fine Arts rises in majesty. In the early morning light, at mid-day, at twilight, and in the shadows of the fading evening light, it is still dream-like - haunting in its beauty. Its curving wings and colonnades of Corinthian columns are like the Greek peristyles of old its dome fantastic Byzantine in the heavy arched effect, and there is a powerful Roman note in the majesty and might of it all. It belongs wholly to no clime, no race, no school. It is a dream of all the beautiful things in the builders' art brought into concrete form. The lagoon before it, mirroring its beauty, is the final touch to this most perfect whole. To the south of the block of main buildings there is the wide-spread approach of the main entrance with its fountains and pools, flanked by two buildings so different and still in such harmonions balance: the Palace of Horticulture and Festival Hall. To the east rises Festival Hall, with the touch of the florid French Renaissance in the days of the Louis', the note of the Orient struck in the outline of the dome. To the west, lifting its opalescent dome in splendid height, Horticultural Hall gives the finest blend of Byzantine, Saracenic and French Renaissance architecture. The domes are of the Orient; the minarets are Saracenic; and the banded garlands, the flowered plaques and the fanciful caryatides are of the French Renaissance, bordering closely upon the characteristics of the Rococo period of this most florid and fanciful time in the arts of France. Throughout the buildings the red tiled roof is in evidence everywhere, the travertine wall; everywhere the windowless front - again all notes of Spain. The long blank wall on the south front has been finely treated, broken in the center as it is by the superb lift of the Tower of Jewels, raising its head over four hundred feet. The eye runs up from terrace to terrace, following the pale jade columns, to the glittering apex topped with a globe. Through the arch, out to the hills and bay beyond, the view is broken by the shaft of the great Roman column - the Column of Progress, topped by the Adventurous Bowman. Half way down on either side on the south front, opening into smaller courts, are delicate towers, their slender forms in airy contrast with the bulk of the massive Tower of Jewels at the center of the wall. These smaller towers are daintily colored in Spanish patine design. In form they are very Italian. To the east, a massive square tower, altar-like in its solemn lines, closes the Court of Ages to the bay. Beyond on the Marina, a fitting close to this gamut of the builders' art in Spain, the last cry in the Spanish architecture of the old day - the California Building - lifts its heavy beams and bastions to its own familiar sky. The adventurers in the new world, in their wish to plant a new Spain upon its soil, tried with the material at hand to rear anew the cathedrals of the older home, and this solemn pile, devoid of ornament, with its heavy doors, its loopholes and its bells, is typical of what they wrought - the Spanish note of the new Spain the Spain that Columbus brought home to his queen. To the west the wall of these mighty palaces is broken by the tree-bordered allee leading into the Court of the Four Seasons, by the two magnificent half domes similar to that in the Court of the Four Seasons, and the small niches in which sit, throned in solitary splendor, the odd figures typical of the plentiful gifts of the earth's harvest and the triumph of agriculture. The wall swells majestically into the two great half domes - one set about with the Figures of Culture, the other with the Lover of Books. Above these the arches of the domes rise beautifully tinted in delicate rose and blue and bossed with the rose of Jericho. Below in each a Spanish poso fountain sends out a shimmering iridescent veil of falling water. Along the eastern wall the view is less romantic, less classic, less reposeful. Iberian bears perch upon the tops of the pilasters, and the finely arched doorways and the foreground of foliage here make up a fine harmony; the floating banners and wonderful lamps a gorgeous color note. Aladdin of the days of old must live again in the lamps of the Exposition. The subterranean garden in which he found his magic lamp, was lighted with fairylike lanterns shining in soft radiance amid the foliage of many trees. The banners richly wrought with heraldic designs and hearing the names renowned in the annals of Spain, form spots of fine color by day - at night, softly glowing, their radiance brings in the thought of Orient lands and their enchantments. The plan of the Exposition and the arrangement of its buildings were dictated by its location. The winds and fogs made shelter imperative. The plan of connected buildings surrounding and forming inner courts, sheltered from the elements, suggested itself. This led to a plan wherein the exterior was plain almost to severity and the decorations were lavished upon the inner courts. This too suggests the Spanish idea, for the barest front, the plainest doorway, may conceal from sight the most beautiful patio gemmed by placid pools and surrounded by fairylike galleries. In conception and in the carrying out of the color scheme, the plan of decoration, and the general design, the Exposition is true to the Spanish type as it has been brought down from the Saracenic and Moorish builders' art through the Spain of the Renaissance. |

|||