| Home -> A. M. Robertson -> San Francsico One Hundred Years Ago ... -> Text | |||

|

San Francisco One Hundred Years Ago

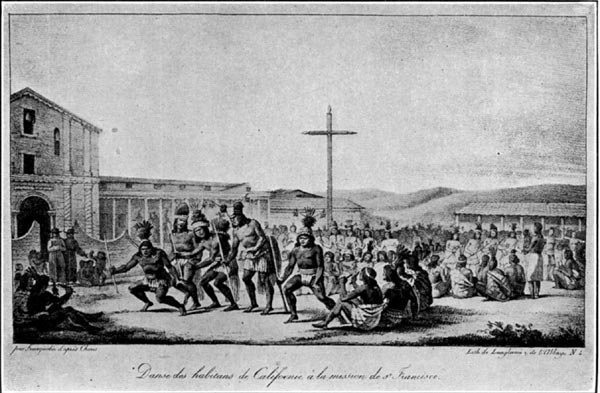

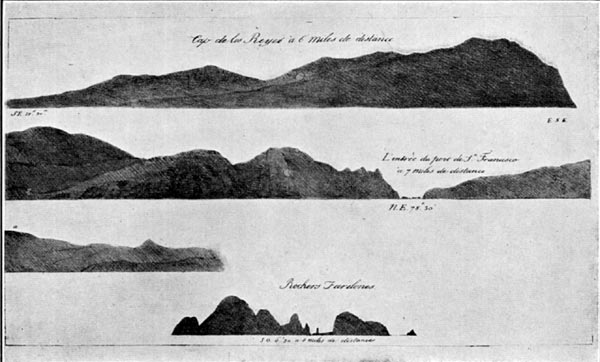

Early on September 20, 1816 (old style, October 2), we came within sight of the coast of New California. The land we first saw was what is known as Point Reyes, to the north of San Francisco. As the wind was favourable we soon passed the Farallones, which are dangerous rocks, and at four in the afternoon we entered San Francisco harbour. The fort, which is within the entrance and on the south shore, is thoroughly equipped for defense. The presidio of San Francisco is about one marine mile from the fort and on the same side; it is square in form and has two gates which are constantly guarded by a considerable company of men. The buildings have windows on the side towards the interior court only. The presidio is occupied by ninety Spanish soldiers, a commandant, a lieutenant, a commissary, and a sergeant. Most of these are married. The men and women are tall and well built. Very few of the soldiers have married Indians. They are all good horsemen and two of them can easily cope with fifty natives. Two leagues to the southeast of the presidio and on the southern shore of the harbour is the Mission of San Francisco, which makes a fair-sized village. The mission church is large and is connected with the house of the missionaries, which is plain and reasonably clean and well kept. The mission always has a guard of three or four soldiers from the presidio. The village is inhabited by fifteen hundred Indians; there they are given protection, clothing, and an abundance of food. In return, they cultivate the land for the community. Corn, wheat, beans, peas, and potatoes - in a word, all kinds of produce - are to be found in the general warehouse. By authority of the superior, a general cooking of food takes place, at a given hour each day, in the large square in the middle of the village; each family comes there for its ration which is apportioned with regard to the number of its members. They are also given a certain quantity of raw provisions. Two or three families occupy the same house. In their free time, the Indians work in gardens that are given them; they raise therein onions, garlic, cantaloupes, watermelons, pumpkins, and fruit trees. The products belong to them and they can dispose of them as they see fit. In winter, hands of Indians come from the mountains to be admitted to the mission, but the greater part of them leave in the spring. They do not like the life at the mission. They find it irksome to work continually and to have everything supplied to them in abundance. In their mountains, they live a free and independent, albeit a miserable, existence. Rats, insects, and snakes, - all these serve them for food; roots also, although there are few that are edible, so that at every step they are almost certain to find something to appease their hunger. They are too unskillful and lazy to hunt. They have no fixed dwellings; a rock or a bush affords sufficient protection for them from every vicissitude of the weather. After several months spent in the missions, they usually begin to grow fretful and thin, and they constantly gaze with sadness at the mountains which they can see in the distance. Once or twice a year the missionaries permit those Indians upon whose return they believe they can rely to visit their own country, but it often happens that few of these return; some, on the other hand, bring with them new recruits to the mission. The Indian children are more disposed to adopt the mission life. They learn to make a coarse cloth from sheep's wool for the community. I saw twenty looms that were constantly in operation. Other young Indians are instructed in various trades by the missionaries. There is a house at the mission in which some two hundred and fifty women - the widows and daughters of dead Indians - reside. They do spinning. This house also shelters the wives of Indians who are out in the country by order of the fathers. They are placed there at the request of the Indians, who are exceedingly jealous, and are taken out again when their husbands return. The fathers comply with such requests in order to protect the women from mischief, and they watch over this establishment with the greatest vigilance. The mission has two mills operated by mules. The flour produced by them is only sufficient for the consumption of the Spanish soldiers who are obliged to buy it from the fathers. The presidio frequently has need of labourers for such work as carrying wood, building, and other jobs; the superior, thereupon, sends Indians who are paid for their trouble; but the money goes to the mission which is obliged to defray all the expenses of the settlement. On Sundays and holidays they celebrate divine service. All the Indians of both sexes, without regard to age, are obliged to go to church and worship. Children brought up by the superior, fifty of whom are stationed around him, assist him during the service which they also accompany with the sound of musical instruments. These are chiefly drums, trumpets, tabors, and other instruments of the same class. It is by means of their noise that they endeavour to stir the imagination of the Indians and to make men of these savages. It is, indeed, the only means of producing an effect upon them. When the drums begin to beat they fall to the ground as if they were half dead. None dares to move; all remain stretched upon the ground without making the slightest movement until the end of the service, and, even then, it is necessary to tell them several times that the mass is finished. Armed soldiers are stationed at each corner of the church. After the mass, the superior delivers a sermon in Latin to his flock. On Sunday, when the service is ended, the Indians gather in the cemetery, which is in front of the mission house, and dance. Half of the men adorn themselves with feathers and with girdles ornamented with feathers and with bits of shell that pass for money among them, or they paint their bodies with regular lines of black, red, and white. Some have half their bodies (from the head downward) daubed with black, the other half red, and the whole crossed with white lines. Others sift the down from birds on their hair. The men commonly dance six or eight together, all making the same movements and all armed with spears. Their music consists of clapping the hands, singing, and the sound made by striking split sticks together which has a charm for their ears; this is finally followed by a horrible yell that greatly resembles the sound of a cough accompanied by a whistling noise. The women dance among themselves, but without making violent movements. |

|||

Californian Air Tremblingly and Mysterious |

|||

|

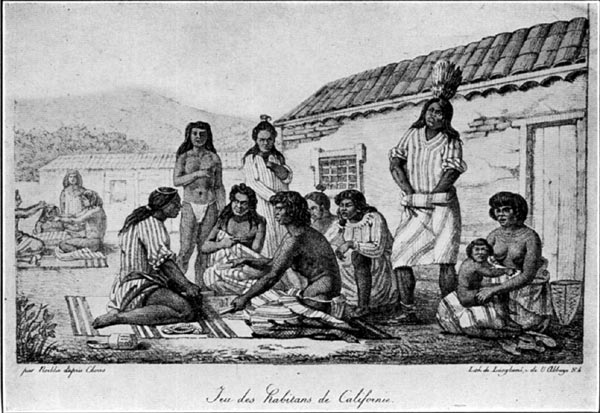

The Indians are greatly addicted to games of chance; they stake their ornaments, their tools, their money, and, frequently, even the clothing that the missionaries have given them. Their games consist of throwing little pieces of wood which have to fall in an even or in an odd number, or others that are rounded on one side and as they fall on the flat or on the round side the player loses or wins.

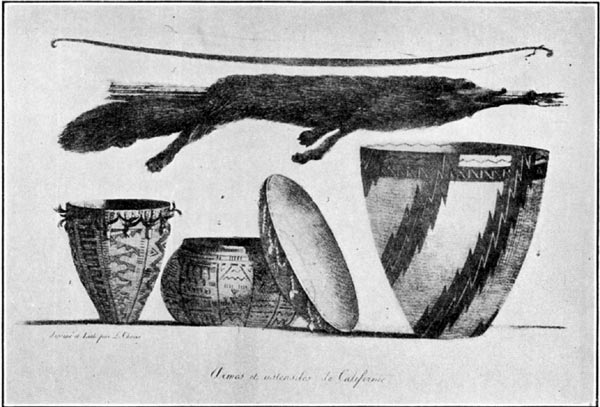

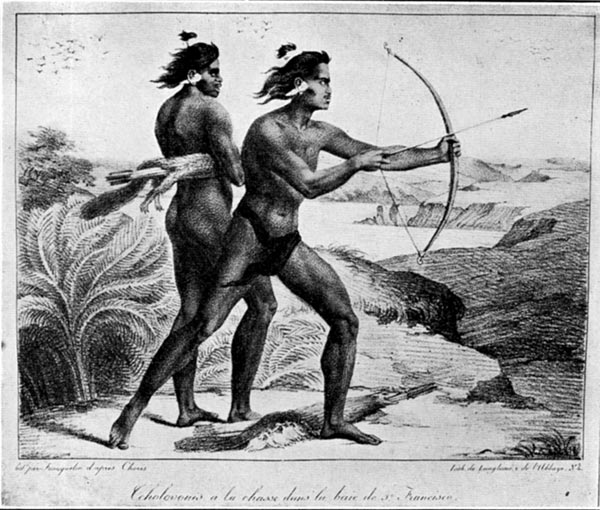

Upon the demise of his father or mother, or of some kinsman, the Indian daubs his face with black in token of mourning. The missionaries have characterized the people as lazy, stupid, jealous - gluttons, cowards. I have never seen one laugh. I have never seen one look one in the face. They look as though they were interested in nothing. It is reckoned that there are more than fifteen Indian tribes represented in the mission. The Kulpuni, Kosmiti, Bolbones, Kalalons, Umpini, Lamanes, Pitemens, and Apatamnes speak one language and live along the Sacramento River. The Guimen, Utchiuns, Olompalis, Tamals, and Sonomas likewise speak one language. These tribes are the most largely represented at the Mission of San Francisco. The Saklans, Suisuns, Utulatines, and the Numpolis speak different languages. Another tribe, the Tcholovoni, differ considerably in feature, in general physiognomy, and in a more or less attractive exterior from all the others. These live in the mountains. They have formed an alliance with the Spaniards against all the Indian tribes. They make beautiful weapons, such as bows and arrows. The tips of the latter are furnished with pieces of flint fashioned with great skill. Severe fevers occur constantly among the Indians. These maladies commonly carry off a very great number. Several missions in Lower California have gone out of existence in the past twenty years by reason of the extinction of the Indians. The Indians at the missions to the south of San Francisco - particularly that of Santa Barbara - make charming vessels and vase-shaped baskets, capable of holding water, from withes of various running plants. They know how to give them graceful forms, and also how to introduce pleasing designs into the fabric. They ornament them with bits of shell and with feathers. The Indians build their canoes when they are about to undertake an expedition on the water; they are made of reeds. When they get into them they become half filled with water so that the occupant, when seated, is in water up to the calves of his legs. They propel them by means of long paddles having pointed blades at both ends. The Missions of San Francisco, Santa Clara, San José, and Santa Cruz depend upon the presidio of San Francisco which is required to succour and assist all the fathers and to furnish them with soldiers when necessary - particularly to accompany them upon excursions into the country. One such expedition, consisting of two fathers and twelve soldiers, returned a short time before our arrival. It had been their intention to ascend the Sacramento River, which empties into the bay to the northeast of the mission. But the Spaniards met parties of armed men at every turn; nowhere were they well received. They were compelled therefore to return after fifteen days without having made any progress towards the end in view. The rocks near the bay of San Francisco are commonly covered with sea-lions. Bears are very plentiful on land. When the Spaniards wish to amuse themselves, they catch them alive and make them fight with bulls. Sea-otters abound in the harbour and in the neighbouring waters. Their fur is too valuable for them to be overlooked by the Spaniards. An otter skin of good size and of the best quality is worth in China. The best grade of skins must be large, of a rich colour, and should contain plenty of hairs with whitish ends that give a silvery sheen to the surface of the fur. Russians from Sitka (Norfolk Sound), the headquarters of the Russian-American colony, are established at Bodega Bay, thirty miles north of San Francisco. Their chief in this new settlement is M. Kuskof, an expert fur-trader. They are thirty in number and they have fifteen Kadiaks with them. They have built a small fort which is equipped with a dozen cannon. The harbour will admit only vessels that draw eight or nine feet of water. This was formerly a point for the selling of smuggled goods to the Spaniards. M. Kuskof actually has in his settlement horses, cows, sheep, and everything else that can be raised in this beautiful and splendid country. It was with great difficulty that we obtained a pair of each species from the Spaniards because the government had strictly forbidden that any be disposed of. M. Kuskof, assisted by the small number of men with him, catches almost two thousand otters every year without trouble. When not so engaged the men are employed at building and in improving the settlement. The otter skins are usually sold to American fur-traders. When these fail of a full cargo, they go to Sitka where they obtain skins in exchange for sugar, rum, cloth, and Chinese cotton stuff. The Russian company, not having a sufficient number of ships, sends its own skins to China (or only as far as Okhotsk) as freight on American ships. Two hundred and fifty American ships, from Boston, New York, and elsewhere, come to the coast every year. Half of them engage in smuggling with enormous profit. No point for landing goods along the entire Spanish-American coast bathed by the Pacific Ocean, from Chili to California, is neglected. It often happens that Spanish warships give chase to American vessels, but these, being equipped with much sail, having large crews, and having, moreover, arms with which to defend themselves, are rarely caught. The commodities most acceptable to the Indians of the coast of Northwest America are guns, powder, bullets, and lead for their manufacture, knives, coarse woolen blankets, and mother-of-pearl from the Pacific which they use to make ornaments for the head and neck. Ships are often attacked with the very arms that they themselves sold, and even on the same day that they were delivered. Most of them, however, carrying from eight to fourteen guns, are able to defend themselves. Such occurrences are frequently turned to profit, for, should they carry off one of the chiefs, they are certain to get a great deal of merchandise as ransom, and gain greater facilities for trading. May Heaven defend a ship from being wrecked on this coast! It is said that the barbarous habit of eating their prisoners survives among several of the tribes that inhabit it. When they build a house, or when they carry out some matter of importance, they put to death a number of slaves as is done when a war is ended. Upon a man's death, they bury with him his wife and the slaves to whom he was most attached. |

|||

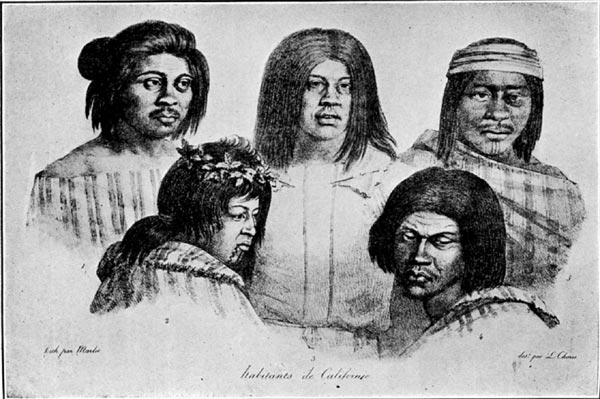

Natives of California (1816) |

|||

A Residence (1913) |

|||

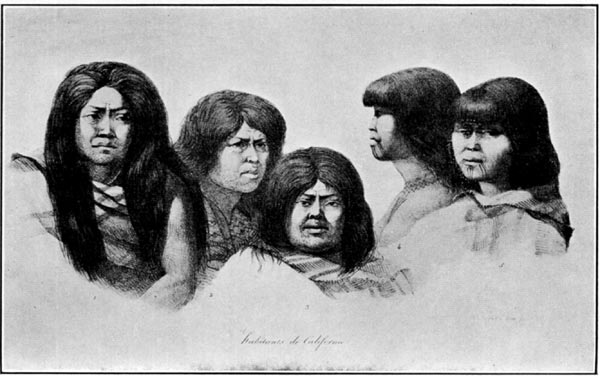

Natives of California (1816) |

|||

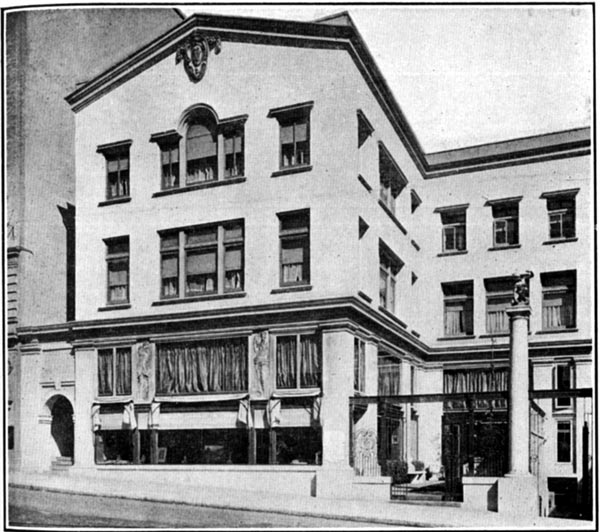

A Shop (1913) |

|||

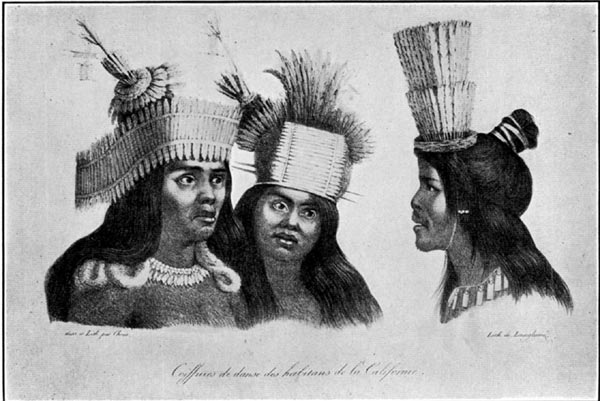

Head-Dresses Worn by the Natives of California in Their Dances (1816) |

|||

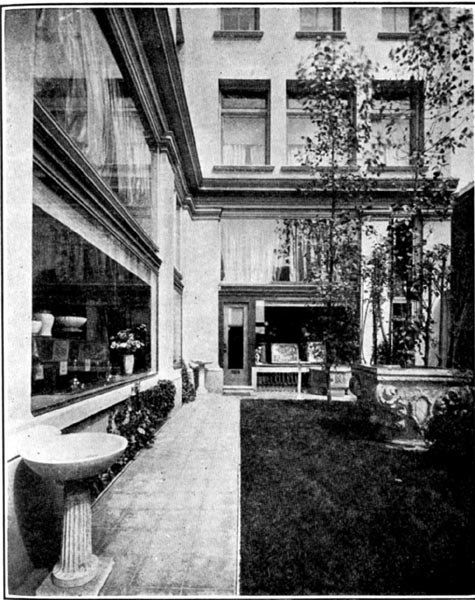

A Shop (Courtyard and Show-windows) (1913) |

|||

A Dance of California Indians at the Mission (Dolores) of San Francisco (1816) |

|||

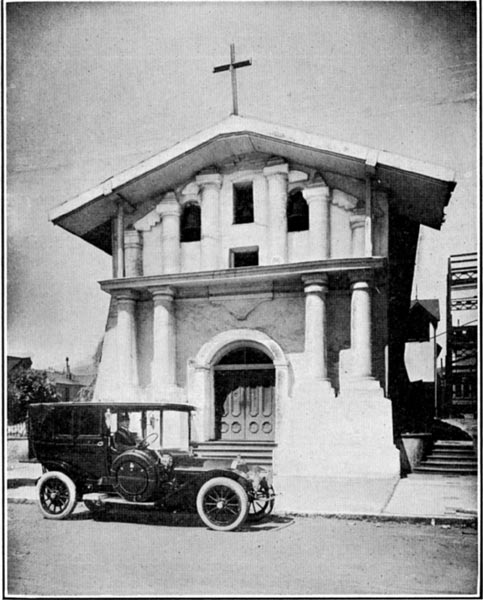

Mission Dolores (1913) |

|||

A Game of the Natives of California (1816) |

|||

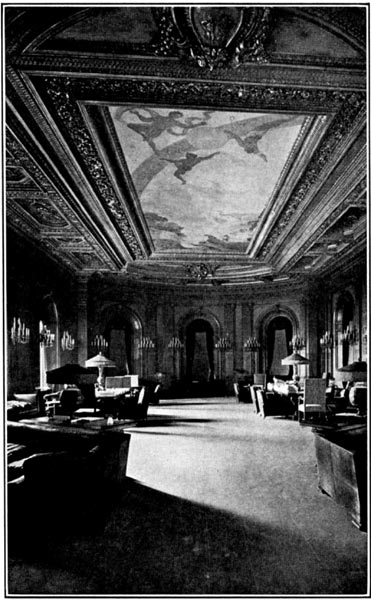

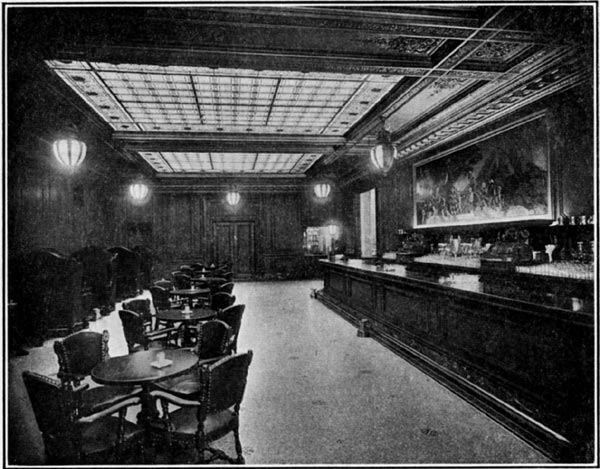

A Club Interior (1913) |

|||

Point Reyes, the Golden Gate, and the Farallones (1813) |

|||

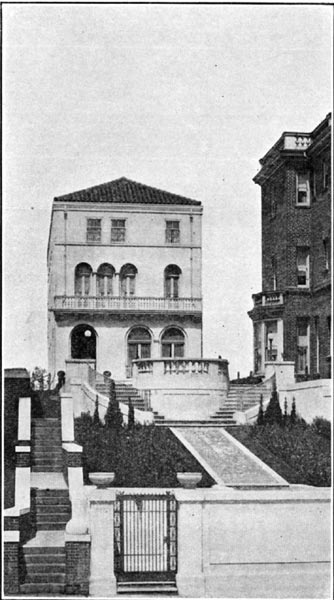

A Residence (1913) |

|||

Weapons and Utensils from California (1816) |

|||

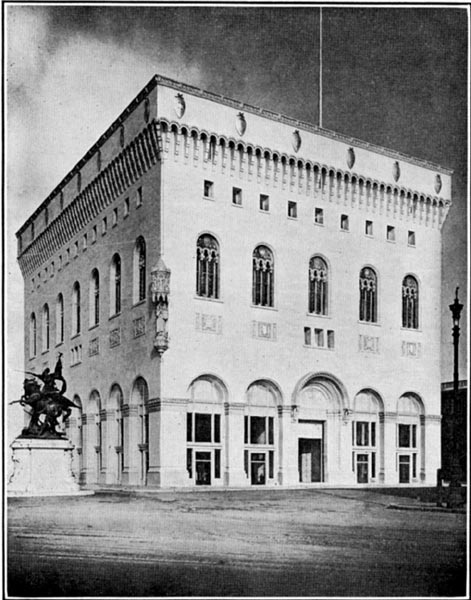

Masonic Building (1913) |

|||

Indians of the Tcholovoni Tribe Hunting on the Shores of the Bay of San Francisco (1816) |

|||

A Hotel Bar (1913) |

|||

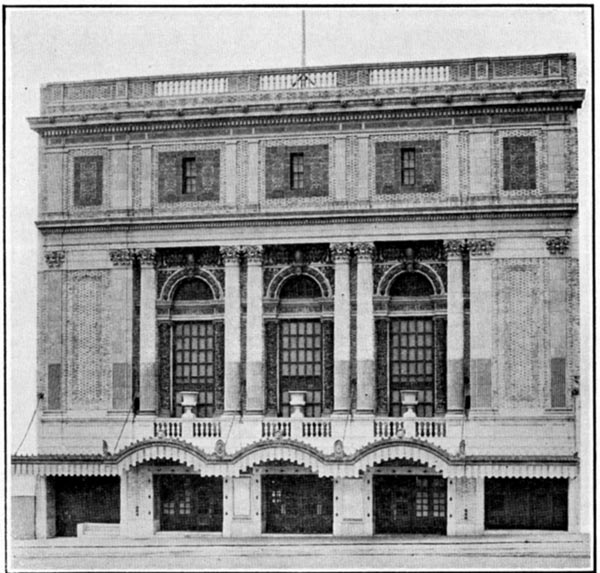

A Theatre (1913) |

|||

Union Square (1913) |

|||

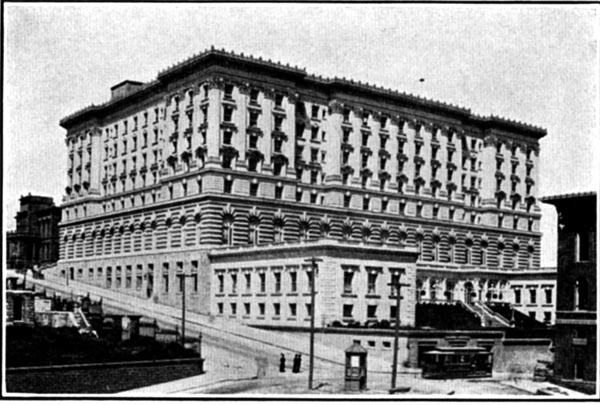

An Hotel (1913) |

|||

|

|

|||