| Home -> Other California Books -> The Denby Children at the Fair - Text | |||

|

|||

|

The Denby Children at the Fair

|

|||

|

|||

|

By Mary E. Bamford

Published By David C. Cook Publishing Company Chicago - New York - Boston Factory and Shipping Rooms, Elgin, Illinois Copyright, 1904, By David C. Cook Publishing Co., Elgin, Illinois. |

|||

|

|||

| Chapter I. "Be careful, Nellie," whispered Mrs. Denby, as she entrusted the hot teapot to the small hands of her eleven-year-old daughter. With the utmost care Nellie carried her burden to the counter, and passed the teapot to the three ladies on the other side. Such tired, pleasant-looking ladies they were! Nellie flew to get another teapot, and to bring the sugar and milk down to that end of the counter. Nellie's mother and Augustus and Nellie herself had come three months before this, from the country to San Francisco, to take charge of a little lunch counter during the Midwinter Fair that brought so many visitors to the great city. The two children had been very helpful to their mother, so far. Augustus did his share of washing and wiping cups and saucers and spoons, and of attending to customers, and never yet had he shirked. This is a great deal to say of a twelve-year-old boy as eager for seeing novelties as Augustus was. There were so many wonderful sights outside the building where Mrs. Denby had her counter, that sometimes Augustus had to look straight at the dishes and rub them very hard to help himself forget how much he wanted to run away and see what was going on outdoors. During the busiest hours Augustus and Nellie had quite enough to do, for many people had found out about the quiet little place where the faucets and the teakettle and the counter shone with cleanliness, and where one could get a hot cup of tea or coffee for five cents instead of ten. Mrs. Denby did not frown, either, or say, "You won't open your lunch-baskets here, will you?" if the customers, instead of buying any of her doughnuts or sandwiches to eat with the coffee or tea, brought their own lunch with them. In short, Mrs. Denby treated people in the way she would have liked to be treated herself, if she had been walking around the fair for hours and had become very weary. Mrs. Denby was business-like in her ways, but when any tired woman helped herself a second time from the little brown teapot that had been handed her, Mrs. Denby never counted the few extra sips or demanded another nickel. Mrs. Denby taught her two willing helpers to be governed by that Golden Rule the Master long ago gave to his followers: "All things whatsoever ye would that men should do to you, do ye even so to them." "Isn't it pleasant to see a boy help his mother so willingly!" quietly said one of the three lady customers to another. Augustus had been washing some spoons at the tiny, shining hotwater faucet, and now, enveloped in a little cloud of steam from the hot water, he was rubbing the spoons dry on a clean dishtowel. His face was rosy with work. Nellie was so near the ladies that she heard what the speaker said. The lady looked up just in time to see Nellie smile. The lady smiled, too. Is he your brother?" she asked, in a friendly way. "Yes'm," answered Nellie, coloring. "And that is your mother, and you both help her?" questioned the customer, with kind interest. "Yes'm," returned Nellie again. "'Gustus won't even ask if he may go away, times when he knows the Indians are out in the street, around the corner from here. 'Gustus loves lndians, and these have their faces painted red and yellow, and they sing so funny! I'm afraid of them, but 'Gustus stays and helps mamma, when I know he wants to go and see the Indians." Nellie's face was bright with pleasure. She was glad to have heard what the lady said about the brother who worked so faithfully. "Do you like the fair?" inquired the lady, smiling. "Yes'm," replied Nellie. Then the smile in the kind eyes opposite won Nellie's trust, and she leaned forward and added softly, "You know, our papa's dead, and there's a mortgage on our house up country where we live. That's the reason we're having this counter. Our minister got mamma this place, so she could earn some money. The mortgage's about a hundred dollars, and 'Gustus and I are helping!" Nellie's eyes were very bright and eager with honest pride in the thought that she could help, but suddenly the eyes of the lady opposite filled with tears and she looked down at her teacup. "Nellie," called the mother's low voice; and Nellie hurried to carry some coffee to a gentleman who had come to the other end of the counter. Augustus still washed spoons. Soon, two of the ladies began fastening their lunchbaskets. The third lady, who was the one that had talked with Nellie, looked toward the little girl now, and held out the money to pay for the tea. Nellie hastened toward her. "Your tea was very good," said the lady kindly, as she put the fifteen cents into the plump hand. "Do you stay here behind the counter all the time? Don't you ever go out to see the fair?" "Oh, yes'm," answered Nellie enthusiastically, "'Gustus and I take turns, afternoons, when mamma isn't very busy. Yesterday I went to see the donkeys and the camels. And I had twenty-five cents that mamma gave me" - Nellie dropped her voice and spoke very confidentially - " and there was a Turk that sold things, and I bought a soup-spoon for mamma. I'm going to give it to her on her birthday that's coming pretty soon. There are black marks all over one side of the red handle of the spoon. You'd never think of such a thing, but the Turk said that the black marks are writing, and they mean, 'My dear friend, help yourself to soup.' I wrote that on a piece of paper, so I shouldn't forget, and I'm going to tell mamma what the black marks mean, when I give her the spoon. 'Gustus has twenty-five cents, but he hasn't bought mamma his present yet." "Well, I hope your brother will find as pretty a present for his mother as the spoon will be," said the lady, smiling. "Oh, I am sure he will," said Nellie. "He tries as hard as ever he can to please mamma." It seems to be a 'try-to-please corner' here at this lunch-counter," said the lady. "You are making it a real booth by the wayside for the weary travelers at the Fair." "And she does it," said one of the other ladies, drawing near, "as though she really loved to do it." "I do love to do it," said Nellie, a bright look coming into her eyes. "I do not know of anything that could be nicer than to help people enjoy the Fair, and at the same time be helping one's own mother." At this a wistful look came to the face of the lady who had first spoken to Nellie, and she said, bending to lay her hand gently on the little girl's shoulder: "God bless you, my child. Your mother is rich in having you, and the world is brighter." And then she turned hastily - so hastily, in fact, that Nellie doubted if the lady heard the "thank you" and the "good-by" that she spoke. But Nellie did not know that in the lady's heart were an ache and a great longing - an ache left by the flitting from out her home of a little girl of Nellie's age, and the longing to once again behold her darling. Sometimes she would say to herself, "Oh! can I wait for heaven's unfolding to see the dear one again!" But seeing Nellie had comforted her. The minister had said to the children, before they went away to the city, "You must try to do your work so kindly and willingly that all who come near you will feel that the love of the Master is in your hearts." Nellie wondered, after the lady had left her, if she had done as the minister said. Did this lady with the sad eyes know how full of love her heart was? That evening, when it was almost time to close the buildings, Mrs. Denby let the two children go outside the pavilion to see the electric lights. The tall electric tower sparkled in all its outline, the great wheel was lit, the wonderful search-lights swept here and there over the thousands of people. Then the lights were extinguished, and the electric fountain began to throw up its beautiful, changing waves of red or yellow, green or violet. "Oh!" exclaimed Nellie, "isn't that pretty! I'm going to call mamma to see it." She ran back into the building. Through the aisles, past the piles of oranges and the other exhibits she sped, till she came to her mother's counter. But where was her mother? Nellie looked around at the shut booths. "Mamma!" she called. There was a low moan. Nellie rushed through the counter's little swinging gate. There sat her mother with a white face. "Oh, mamma, mamma! What is the matter?" cried Nellie, terrified, as she sprang to her mother's side. A faint moan was the answer, as the mother leaned back against Nellie and closed her eyes. |

|||

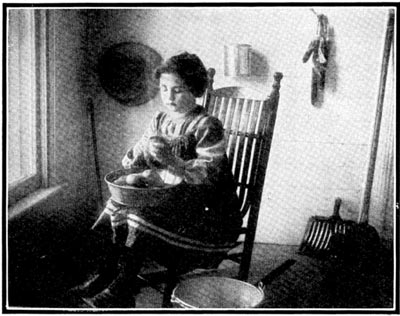

Nellie was so near she heard the speakers. |

|||

| Chapter II. "You have worked too hard," declared the landlady to Mrs. Denby, after the night watchman had showed Augustus and Nellie how to put water on their mother's head to help bring her out of her fainting spell, and after a kind jinrikisha man had carried her in his queer cart outside the fair grounds to the opposite lodging-house where Mrs. Denhy and the children roomed. "I know it," answered Mrs. Denby faintly, as she lay on the bed in her room, "but I couldn't help it. But I'll be all right tomorrow." She smiled at the anxious faces of her two children, and Nellie burst into tears of relief. It had been such a shock to find her mother so ill! But she really did look better now. She was not so pale. "There! there!" the landlady said to Nellie, patting her head. "You and Augustus must help mother all you can. You ought to do a good deal." "We do," stoutly asserted Augustus, who was holding his mother's hand, on the other side of the bed. After the landlady had gone, and the light was out, and Augustus was asleep in his bed, Nellie lay awake a long time beside her mother, and thought and planned. "I do believe that in the time when there isn't so much work, in the afternoon, Augustus and I could take care of the counter our own selves for a couple of hours, without mamma," thought the brave little girl. "That's the time she's let Augustus and me have turns going out to see things, but it doesn't make any difference. We must stay in, and let mamma go somewhere to rest. I know where there's a lounge in one of the county sitting-rooms. Mamma could go there and lie down, maybe, two or three hours every day. If she couldn't go there, she could come here to rest. I'll speak to Augustus about it the first thing in the morning. We've been here three months, and mamma's just tired out - that's what's the matter." Augustus, when spoken to by his sister, agreed to her plan. He had been too thoroughly frightened about his mother to object to doing anything that would help her to gain strength again, though it was a hard thing for any boy to plan to give up his only hours of recreation. It was a harder matter to obtain Mrs. Denby's consent, but when she tried the plan the next afternoon, and after a short rest came back to the counter and found that neither of the children had scalded the other with the boiling water or the hot tea or the steaming coffee, that they had not taken in any counterfeit money or given the wrong change to anybody, that not a plate or cup or saucer had been broken, and that both children were as happy as could be over the money they had taken in, the mother drew a breath of relief. The children were really careful. "You'll let us try it every day, won't you?" pleaded Nellie. "Do, mamma! I like to be a real trader, my own self;" and the little girl beamed at the shining yellow teakettle and the twinkling faucets. "It rested me very much," said Mrs. Denby. "You are both very thoughtful, and when I see you working so faithfully I say, 'Thank God for such dear little helpers.'" But the mother looked very frail and weary, for all her effort to appear well, as she tied her white apron and began preparations for supper. She sent Nellie and Augustus for a short run outdoors. The fresh wind that kept the multitude of streamers and flags fluttering on the tops of the buildings seemed very pleasant to the children, after having been indoors so long. They found a funny, fat little Eskimo boy, around one corner. He belonged in one of the white, round-topped huts that looked like immense eggs cut into halves and set on the ground. These huts were covered with white canvas to represent the snow out of which Eskimos make their winter homes. Around the dome-shaped huts, hiding them from the road, was a fence, while at the gate of the enclosure waited a number of black-and-white Eskimo dogs and a wooden sledge, to give visitors a ride to the white-topped huts. The little boy whom Augustus and Nellie found was only about two and a half or three years old, they thought. He threw back his head and opened his mouth very widely and showed his white teeth, when he laughed up into Nellie's face. He held out a tiny pair of sealskin shoes, about big enough for a doll. He was imitating his mother, probably, in trying to sell them, and he was so plump and friendly a little trader in his queer Eskimo clothes that Nellie felt as if he and she were quite acquainted immediately. "If he can do trading, I guess you and I can, Augustus!" she laughed. "We're a good deal older than that baby!" The Eskimo boy chuckled as if he understood, though of course he did not, and the children hurried back to their counter. Mrs. Denby had not intended that the children's plan of afternoon rest for their mother should become a reality, but as the days went by and the mother's strength did not return to her, it grew to be a customary thing for the children alone to attend to the counter for a couple of hours every afternoon. Nellie was jubilant over every customer that came, and Augustus presided over the business with a gravity that showed how anxious he was to do his best. Neither of the children dreamed that when the keeper of a booth came by and gave them each an orange, and when the old janitor praised them as being "right smart children," and when the man who made glass pens said warningly, "You keep your counter slick, now, for I am coming to get my coffee of you!" all these kind people said to themselves, "Poor little folks! Poor little folks! They are doing the best they can. But that mother of theirs looks a sick woman at times." To the children their mother seemed better. She did not say anything to them about any pain. They thought her comfortable. "We're helping her to get well again!" Augustus would say to Nellie; and that thought aided both children to work bravely through each week. Some afternoons when there was a lull in the business, just after everyone had had the noontide luncheon, and it was not quite time for tea, Mrs. Denby would say, "Now we will all rest together." These were beautiful times for the children and for the mother. The children called it their "golden hour," and it was a golden hour to all three. Sometimes they would stop at the grounds where the donkeys stood waiting and enjoy a short ride. At other times they would seek the sands where the wind from the Golden Gate blew refreshingly in upon them. There where the large stone cross stands in memory of Sir Francis Drake, the ancient discoverer of San Francisco Bay, they would sit down and have a quiet time together. Sometimes they would bring their lunch, and when this was the case, they would feed the crumbs to the birds, which gathered thickly around them as soon as they saw this luncheon. "Mamma," asked Nellie one afternoon as they all sat together on the sands, "do you think that we shall get enough money for the mortgage?" "We have done very well so far," answered her mother. "There are three months left yet to try in," said Augustus hopefully. "Only half of our time has gone." Mrs. Denby smiled at the tone. Augustus was becoming very manly in his feeling of care and protection toward his mother. "You and Nellie are my dear helpers," she said. "I should have to give up the counter, if it were not for you. I am sure I should." "Oh, mamma!" cried Nellie, throwing her arms about her mother's neck, "we love to do it! Don't you remember our minister told 'Gustus and me that we must do all the good we could at the fair? And he said that if it was only wiping dishes behind our counter, we could do it carefully for Jesus' sake. Won't our minister be surprised when he hears that 'Gustus and I really kept the counter some afternoons! Oh, mamma, shan't we all be so happy when the fair's over, and all our mortgage's paid, and we go home together!" Her mother looked at the little girl. Something in the tenderly wistful gaze struck Nellie. What made her mother look so? And why did she not answer, except by that look? |

|||

Where the Donkeys stood waiting. |

|||

|

|||

|

|||

| Chapter III. "Mamma," questioned Nellie one day, as Mrs. Denby and the two children sat again upon the sands, "You are better, really, aren't you? You won't ever frighten us by fainting again, will you?" The look that Mrs. Denby's face had worn the day they were last on the beach had troubled Nellie all the week. To-day, seeing how weak and tired her mother appeared, Nellie suddenly had wondered if the afternoon rest was really helping her as much as Augustus and she had hoped. Was their mother better? Mrs. Denby did not answer Nellie for a little while. Her face was partly hidden by the end of one of the folded shawls against which she was half leaning as upon a cushion. Nellie sat watching the children playing on the sands. By and by she put back the shawl from her face, and said, quietly, "I want to tell you something, children. Come a little nearer, Augustus, and you, Nellie. Sit here." When the two children were very close to their mother, and her arms were about them, Mrs. Denby rested her head lightly on Augustns' shoulder, and went on, softly: "A number of years ago, a young man and his wife had a pleasant home together. One happy day God sent a little boy to the home, and the Father and mother were very glad, and they said, 'We will call our boy Augustus.' After a while there came another happy day when God sent a little girl to the home. The father and the mother and even baby Augustus were very glad, and the little girl was named Nellie. The years went along till the two children were partly grown, and then the dear Lord said to the children's father, 'Come.' But the father said, 'Dear Lord, who will take care of my two children and my wife, if I die? I cannot die and leave them.' And the Lord answered, 'I am the Father of the fatherless, and the widow's God. Leave thy fatherless children: I will preserve them alive; and let thy widow trust in me.' And the children's father said at last, 'Dear Lord, I trust my wife and my children to thee. Thou wilt take care of them.' Then the children's father went away, for God called him. And the Lord kept his promise, for he took care of the children and of their mother, just as he had said he would. "After several years" - the mother's voice faltered for on instant, but she recovered herself and went on in a quiet tone - "the children's mother began to feel less strong than in the early years of striving to take up the burden the father of the home had once borne for her. She began to wonder if it could be that she was not going to hold out in the struggle of gaining a home for her loved ones. It almost broke her heart as she thought it might be possible that she too would be called away, as had the loved father. Again and again she cried, 'Oh! I could not, could not leave them! They are so young, and with their father gone they need a mother.'" She stopped speaking, and Nellie nestled closer, while Augustus looked out over the water as though be feared a little what might be coming. "And then - " "But even as she cried thus, a voice seemed to say gently, 'Lo! I am with you alway,' and the heart of the mother was comforted. She was sure that, whether she was called to leave her children, or permitted to stay with them, she trusted everything in the kind Father's hands." There were tears now on Nellie's face, and Augustus had turned toward the water. His sister gave a swift glance toward him and felt sure he was crying "Mamma," she said, throwing her arms around her mother, "you must not leave us! You will get well." And the mother gathered the little girl to her closely and said: "We will trust Him, dears - just lay our hands in His and he led day by day. And whatever comes, we will feel that it is right. Can you do that, my boy?" Augustus drew a long breath and rose to his feet. "It is growing cool, mother," he said, gathering up the wraps. "It is time we were going back." "But you will trust him, Augustus?" Thus pressed for an answer, the boy said: "I will try, mother." But even as he spoke, tears fell from his eyes, and he broke from his mother's detaining hand and ran on ahead. During the following days the children watched over their mother with extreme care, but she was so cheerful, as she attended to the work behind the counter every morning, that it seemed impossible to Augustus and Nellie that Mrs. Denby was really in danger of serious illness. They did not know how hard it was for her sometimes to smile, or to overcome the feeling of utter exhaustion that would almost overpower her before the busy noon hours were over and she could go away to lie down. It was in the afternoons, between customers, that the loneliness and trouble most weighed on Nellie's heart. It seemed to her that if only Augustus and her mother and herself were in their little country home, the days would not be so lonely as they were now. They saw so many people here at the fair every day, and yet they were almost all strangers. It was not as it would have been at home, where the kind-hearted neighbors would have come to see Mrs. Denby, and would have told the children what to do for their mother. "Maybe there's something Augustus and I could do for mother, if we only knew what it is," Nellie would think sorrowfully in the afternoons when her mother's absence caused a homesick feeling that was almost insupportable, "but here there isn't anybody but our landlady to tell us what to do, and she's so busy she hasn't time." One afternoon as Nellie, from her counter, was looking with sober face down the long passageway, she spied two people coming. She looked again. They were two people from her own little country town. "Augustus!" she cried excitedly, "there's our minister, and there's Mr. Hastings!" Chapter IV. "Well!" cried the minister, as Nellie rushed down the passage, her face flushed with excitement, "here comes one of the shop-keepers! Is this the way you fly out to catch customers?" Nellie laughed, and then he shook hands with Mr. Hastings, who was her Sunday-school superintendent at home. Then the superintendent and the minister, Mr. Stanhope, came straight to the lunch counter, and shook hands with Augustus, and sat down. "I've seen a Sandwich Island grass house, and I've seen a wonderful machine that was making a red whip from a number of red spools that danced around in and out among one another as if they were crazy," said Mr. Hastings, who was a very jolly man, "and I've seen ladies riding in jinrikishas, and a man ride on a camel, and a Turk made me buy a wooden fan to hang up at home. A Turk stared at me out of a sedan-chair, and I heard the South Sea Islanders beating their drum on the street. I'm hungry. I want some coffee, Nellie, and some doughnuts and some sandwiches; and Mr. Stanhope wants some coffee, too, and doughnuts. All we have had to eat while we have been going around was the least little cup of beef-tea apiece. A girl was giving away beef-tea at one stand, and she gave us cups that were about big enough for fairies! Her beef-tea was so good I could have taken a coffee cup full." Nellie laughed at Mr. Hastings' woeful face. "The beef-tea girl can't give folks much," she answered. "It's just for advertising, you know, to make you buy a can. I guess you didn't find the biscuit stand, where the girl makes lovely little biscuit, and gives you one or two, cut open and buttered." "No," returned Mr. Hastings dolefully, "no, we didn't find that stand. I suppose, if we had, we would have found that the biscuit were about big enough for dolls to eat, wouldn't we?" Nellie laughed again. It was so easy to laugh now, when she and Augustus were hurrying to put lunch before these two dear friends! "Your mother isn't here this afternoon?" said Mr. Stanhope of Augustus, as the boy carefully put two cups of coffee on the counter. "She's lying down, resting," answered Augustus. "Nellie and I take care of the counter, afternoons." Mr. Stanhope poured his cream in silence. "I am glad she has two such helpers as you are," he said at last. "I thought it was about time some of us were coming to the fair to find out how the counter is getting along. But I don't see that we can offer any suggestions about the counter, Mr. Hastings. Everything seems to be going along as smoothly as possible. Don't you think so?" Mr. Hastings looked around him and sighed heavily. "I did hope that I might be able to give these young traders some advice," he answered, "but when I see that their counter is kept scrubbed cleaner than I should probably want to scrub it, and Augustus gives me better coffee than I can make, I don't know what advice to give!" Augustus laughed. "I scrub the counter every morning, as hard as I can," he stated proudly. "Bravo!" applauded Mr. Hastings. Then a little silence fell upon the group. "How is your mother now, Nellie?" questioned Mr. Stanhope in a different tone. "I - I don't know," replied Nellie; and then something in the kindness of the minister's tone brought back the remembrance of that Sunday talk with her mother on the sands. The remembrance overcame Nellie, and her lip trembled, as she said, "My brother and I are doing all we can." "That is good," returned Mr. Stanhope. "Do you think we may see your mother?" asked Mr. Hastings; "or is she too tired?" "Oh, I know she'll be so glad to see you!" exclaimed Nellie. "I'll show you where the rest-room is." Both Mr. Hastings and Mr. Stanhope seemed to be in a hurry, after that. They finished their lunch very quickly, and then Mr. Hastings insisted on paying for what they had eaten, though the children protested against receiving any money from such friends. "We were so glad to see you! We didn't mean you to be customers," objected Nellie, looking at the money. "Are you so particular about choosing your customers?" laughed Mr. Hastings. "Come, show us where your mother is, Nellie." Nellie led the way to a county parlor, upstairs in another building, where Mrs. Denby was resting. She was very thankful to rise and sit in a rocking-chair, and talk with her friends. The minister and Mr. Hastings were shocked when they saw how badly Mrs. Denby looked, but they did not say anything to her about her health, till Nellie had run away down the stairs. "If I could only keep strong," said Mrs. Denby to her two friends, "we have done well. We have a good many customers, and I have saved forty dollars toward our mortgage, besides paying our expenses. We have been very careful and economical and the children have been a great help. But you see how weak I am. It seems to me sometimes that I am going Home, and yet, when I think of leaving my two little children - " She could not say any more. Mr. Stanhope and Mr. Hastings stayed and talked with her for a while. Afterwards the two men walked along over one of the roads of the fair, and talked a long time with each other. Their faces were very sober. "If Miss Ruth would do it, it would be a great thing for Mrs. Denby and those children," said Mr. Stanhope at last. "My sister will do it, I'm certain," answered Mr. Hastings. "She's always ready to enter a door that leads to help for someone. I will write to her about it at once. She will drop everything and come, I am sure." Then the two men talked of another part of the plan that they were forming for Mrs. Denby and the children. Mr. Stanhope and Mr. Hastings were very thankful they had not delayed any longer in coming to the fair. |

|||

Riding in a Jinrikisha at the Fair |

|||

| Chapter V. This was the plan: Young Mr. Hastings' sister Ruth should be asked to come and take charge of the counter in Mrs. Denby's place. Augustus and Nellie could help Miss Ruth, and they could all room at the lodging-house, as the children and their mother had done heretofore. Mr. Stanhope knew of a hospital in the city where Mrs. Denty could go for a while to see if the doctors there could not help her. The children would not be able to see their mother more than once a week, however. "It is a great deal to ask of Miss Ruth. Do you think she will be willing? They will be very lonely," said Mrs. Denby sadly, when, after a few days, the plan was told to her. "She will come," said Mr. Hastings. "She has written that she will." When the postman brought Miss Ruth the letter, she was greatly surprised. But, as her brother had said, she liked to help others, and when she saw an opportunity to do anything for the love of Christ, she tried to do it. She hastily made ready for the journey. But it was very hard for Augustus and Nellie to give up their mother. It seemed to them that her going to the hospital was like having her taken away from them to die. It was only after the minister had taken both children into his arms, and had gently said that their mother's going seemed to be the only way in which there was any prospect of her being cured, and that the separation was very hard for her as well as for them, but the Lord would help them bear the loneliness, that Nellie threw her arms around her brother's neck, and sobbed, "Oh, 'Gustus, we did ask Jesus to make mamma well! I didn't suppose she'd have to go away from us to get well, but maybe we must let her go!" "That is right," said the minister, huskily, as he drew Augustus closer. "Now, dear little folks, let me tell you one thing. There never is a time in our lives so sad that we cannot look around us and find some work to do for our dear Master. He loves you, and he knows just why he sends you these sad days. Don't you think you can ask him to keep you from crying when mother goes away? It will make her feel worse about leaving you, if you cry. I want you to think, when you see her leaving you, 'Perhaps this is part of the way God is answering our prayer to make mamma well again.' Won't that thought help you to be cheerful before her? Perhaps God is going to give you just what you asked for - a well mother again - but you must let him give her to you in his own way. We should never tell God how he must give us a thing." Nellie sat up and choked back a sob. Mr. Stanhope read in her face that she meant to follow his advice. Augustus could not help sobbing silently still. The minister knew how sore the boy's heart was. "You must remember," Mr. Stanhope reminded the children, cheerfully, "that you can go to see your mother every Saturday afternoon, and you can write her letters in the meantime. The fair will last about three months longer, and by the time it is over, I hope, if it is our Father's will, that you may find your mother much stronger than she is now, and that your mother will be surprised to see how much money her boy and girl have helped earn toward the mortgage. Isn't that a delightful thought? Can't you think how pleased she would be to hear how you have worked while she was away?" But with all the cheering thoughts and all the courage and determination that could be summoned, the day when Mrs. Denby was to be taken to the hospital was a very sad one for the two children. They managed to keep from crying while they clung to their mother for the last kisses, and Nellie waved her hand to the white face lying back in the carriage, as it was driven away, and called, "Good-by, dear mamma. Come back well!" But the moment Mrs. Denby was out of sight, the children burst into tears. "Oh, do you suppose she ever will come back?" sobbed Augustus. "Oh, mamma, mamma!" moaned Nellie, her courage failing, now that the one whom tears might have hurt was gone. "There, there!" soothed Miss Ruth, who was a pleasant young woman. "Come, now. Let's go right over to that counter and begin work. You know you must teach me how you've been used to doing things. I haven't learned the ways of this fair, yet. We haven't any too much time to work, either. Just think of the money we want for that mortgage! Don't fret about your mother any more. The doctors can do a great deal more for her than you can. They'll take good care of her. 'Most the only thing you can do for your mother now is to set right to work about that mortgage money. Let's try to raise it all, and be ready to pay it before mamma knows it! Wouldn't that be fine? Let's hurry over to the counter. We're late this morning, you know, and I have everything to learn; and if we should lose any customers this first day, I declare I would be sorry!" With this cheerful flow of talk, Miss Ruth hurried the children to their usual place of business. In her efforts to turn their thoughts, Miss Ruth asked all the questions she could think of about the faucets, and the electric lights, and the best hours for customers, and how many to expect for lunch at noon, and which kind of sandwiches to make, and what kind of coffee was used. Miss Ruth was as lively and cheerful as could be, though privately she felt a good deal like crying herself, when she looked at the two children, for she knew very well how seriously ill their mother was. "At least, I'm glad I'm here!" she thought. "It's something to the children to have somebody with them that they've known before at home. It'll take off the homesick feeling a little, anyway; and keeping busy will comfort them some more." To put the children immediately to work was one of the wisest things Miss Ruth could have done. But there is better comfort than even work can be. Miss Ruth did not know that, as Nellie tied on her white apron, ready to begin the day behind the counter, the little girl whispered to herself, "Oh, Jesus, help me to hold up Miss Ruth's hands, just as I did mamma's!" |

|||

When the postman brought Miss Ruth her letter. |

|||

|

|||

| Chapter VI. Miss Ruth insisted that Augustus and Nellie should go out and see the fair every afternoon. In the mornings and busy noons she needed the children, but she made them feel that it was their duty to be out in the air several hours each day, for health's sake. "You have been used to running outdoors in the country," she said, "and this salt breeze is good for you. It was right that you should stay in when your mother needed rest, but now I want you to go out more. You will be sick yourselves, if you don't." So the children saw more of the fair than hitherto. The minister and Mr. Hastings had gone back to the country, so there was no one whom the children knew in all the great crowds that Augustus and Nellie met. The children looked for things to write about to their mother. Augustus noticed, before the door of the Chinese building, the queer plants with stems curving like the letter S. Once the children climbed to the roof of a county building, and, looking down, saw a number of Indian children in a field by some tents. They did not seem to be having a very good time. In Cairo Street, the children found traders as young as or younger than themselves. But most of all Augustus liked to stand and watch the camels rise with disapproving grunts and trot off with jingling bells, when someone was taking his or her first camel ride. The shouting of the donkeymen and the camel-drivers and the laughter of the lookers-on, made the spot a lively one. Augustus told his mother about it, the first Saturday when the children went to the hospital. They found their mother lying down, and looking much the same as when they had seen her last. She laughed a good deal over Augustus' tale about the camels, and the children went away happy, because she seemed so. But the next Saturday, when Augustus and Nellie came, they could only slip softly in and see their mother's pale face, as she lay sleeping, under the influence of an opiate, the nurse said. The children were sadly disappointed in not being able to speak to their mother, and all their fears concerning her revived. And when another Saturday went by, and another, without their being able to see their mother, not all the marvelous visions of the fair could dispel the shadows that hung over the days. Nellie's red spoon, with its black, Turkish inscription, still lay hidden, for Mrs. Denby's birthday came and went during this sad time of separation. Miss Ruth tried to take the mother's place, but the children, she saw, found it hard to keep up their courage. Even though every Saturday night showed some little saving toward the mortgage, Miss Ruth grew worried. "The children are grieving themselves sick," she said to herself. "I wish I could divert their minds." But Miss Ruth was not quite prepared for the change that did come. One day Nellie, who had not been feeling quite well for a little while, dismayed Miss Ruth by coming down with what seemed like the measles. How or where the little girl had been exposed, Miss Ruth could not tell, but there was little doubt as to the disease. As Augustus had never had the measles, it was necessary that the two children should be separated, and as Miss Ruth could not leave the lunch-counter to care for itself, matters would have been in a somewhat perplexing state, if the landlady of the lodging-house, Mrs. Rollins, had not volunteered to look after Nellie in the daytime. Nellie was placed by Mrs. Rollins in a small room, and there the little girl was left alone a great part of the day. Mrs. Rollins tried to prevent her from feeling lonely, but there were a good many rooms to be attended to in the lodging-house, and she had half a dozen boarders among the employees of the fair, and so she could not be with Nellie often. Nellie did not find it very interesting to lie there in the half dark, her head aching, and her cheeks a little feverish, and wonder how many customers Augustus and Miss Ruth would have that day. Mrs. Rollins had said that folks who had the measles stayed in bed anywhere from three to eight days. "I hope I sha'n't have to stay eight days," thought Nellie restlessly, as the long hours passed. She knew she could not see Augustus again for more than a week, probably. She had never been ill before without her mother being near, and it seemed to Nellie that if only she could feel her mother's cool hand passing over her feverish forehead, half the trouble of being sick would be over. Nellie cried a little, out of pure lonesomeness and weakness. Then she resolved to be brave. She tried to sing a little, to help pass away the time. She sang softly at first. It did not make her cough much, so she sang a little more loudly: "Only an armor-bearer, proudly I stand." A slight clapping sound came from somewhere. "Sing some more," invited a voice that, though friendly, was unexpected. Nellie was quite startled. She kept silent. "Won't you sing some more, little girl?" asked the same voice, after a while. "Where are you?" questioned Nellie, timidly. "I'm over the other side of the wall," was the answer. "The transom between us is open, you see. Mrs. Rollins has the door nailed up now, because she rents the rooms separately, but I've been listening to your singing ever since you began. I'm sick, you know." "Why, I'm sick, too!" responded Nellie. "I have the measles. Have you?" There was a laugh that was half a groan, over the other side of the partition. "I'd think myself lucky if it was only the measles that ailed me!" replied the voice. "I broke my leg over at the fair grounds, when I was helping put up a building a while ago. I've been lying here weeks. Mrs. Rollins and some of the men are real good to me, but I'm lonesome enough, a good many times." "I was lonesome. That's the reason I was singing," confessed Nellie. "Well, sing again, won't you, and drive the lonesome away from both of us?" petitioned the voice; and Nellie, full of pity for the man who had been ill so long, began to sing, "The Light of the World is Jesus." "Say!" called the voice when Nellie had finished, "don't you know any besides those Sunday-school songs?" "Why, yes," returned Nellie, "I know 'Columbia, the gem of the ocean,' and 'Rally 'round the flag, boys,' and 'My country, 'tis of thee,' and ever so many more." "Well, why don't you sing them, then?" somewhat fretfully demanded the voice. "I will, if you want me to," agreed Nellie. "Only the other kind are dearer, you know. That's the reason I sang them." She sang other songs till there was a rapping on the wall. "You mustn't sing any more," the voice warned. "You're getting hoarse. I'm much obliged to you. You've sung my lonesomeness away." "Mine's gone, too, mostly," responded Nellie. "I was going to write a letter to my mamma, who's in the hospital, you know, but my eyes were bad, and I sang, instead of writing." "Is your mother in the hospital?" questioned the voice. "Maybe, if you'd tell me what you want to say, I could write the letter for you, to pay for your singing to me. That would be only fair, wouldn't it?" "Oh, I'm much obliged to you," answered Nellie, but I'm 'most afraid that my mamma is too sick to read my letter, anyway." Her voice trembled a little, and perhaps the other invalid noticed it, for his tone was quite gentle as he said, "It's hard work having the measles without your mamma, I suspect. How old are you?" "Eleven," returned Nellie, keeping back a great sob that wanted to break her voice. "But my mamma doesn't know I'm sick. We're not going to let her know." "I'm twenty, and my mother doesn't know I'm sick, either," said the other voice, with a queer sort of a laugh, "and I'm not going to let her know!" "Couldn't she come to you?" asked Nellie. "It's so much more comfortable to have your mamma around when you are sick!" There was silence for a moment. Then the young man's voice said, rather indistinctly, "I don't think my mother would want to see me." |

|||

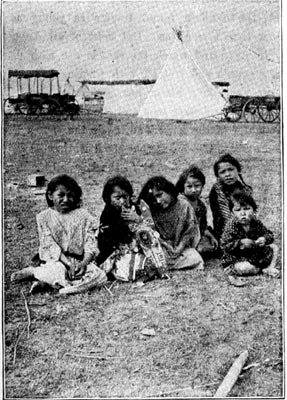

Eskimo Children - Off by themselves |

|||

| Chapter VII. Nellie had become so tired with the exertion of talking and singing that she was glad of the long silence that followed. Her head had throbbed so painfully with fever that she had not more than half understood what the young man said about thinking his mother might not want to see him. Nellie's eyes ached, but at last she dropped asleep, and did not waken till Mrs. Rollins came in. After Mrs. Rollins had gone, the weary, feverish hours lengthened. Miss Ruth managed to leave the stand a moment with Augustus, and came over to see how Nellie fared. Then the child was alone again. But she was so drowsy that she did not care much now whether anyone else was present or not. For the next two or three days Nellie slept most of the time, only waking to ask for a drink, when Mrs. Rollins was near. The fourth day the measles were showing finely on Nellie's chin, and she had a hard, dry cough that the young man over the other side of the partition listened to in sympathizing silence. "Poor little thing!" he said to himself, as he heard her hoarse voice speaking once in a while. Three or four days afterwards he heard Miss Ruth say to her small patient, "There, Nellie, dear, there isn't one of those red spots left on your face or neck! You'll be well before long, now." The next day, the sound of a faint humming came through the wall. "Hello!" called the young man. "Is the singing-bird beginning to chirp again?" "I'm not a singing-bird. I'm just Nellie," said the little girl. "Don't tire yourself talking to me. You are not strong enough yet," said the other. A while afterwards he heard her singing softly and a trifle hoarsely to herself. By listening he could barely catch the words: Have we trials and temptations?

"Tell me the old, old story." The young man's head rested uneasily on his arm. He must stop this singing. He could not stand it. "Nellie," he called, "how are your eyes?" "They're almost well," came the response. "I'm glad you're able to talk again," continued the young man, "Your cough has been some company for me, though." "A cough is queer company!" laughed Nellie. "Oh, I don't know," returned the young man. "I'm used to making company out of almost anything! I got used to it when I was a sheep-herder down on the San Joaquin Plains. I didn't see anybody but my sheep and my dogs and the coyotes for weeks sometimes. I didn't have much of anything to read, either." "Couldn't you get any letters?" asked Nellie. The young man coughed in a rather embarrassed way. "My mail wasn't very extensive," he answered. "No, I never had any letters." "I should have thought your mother would have written to you," said Nellie. "My mother would, I know, if I'd been away off with sheep and coyotes." "It wasn't my mother's fault she didn't write to me," stated the young man, hastily. "How is your mother, Nellie?" "She isn't any better, Miss Ruth says," returned the little girl's voice. He fancied she felt badly, and he hastened to say something else. "You've been singing hymns again," he said. "Is that the only kind of tunes you are going to sing while you are sick? What makes you sing hymns?" "Why, I like to," answered Nellie. "Don't you?" "No," replied the young man, "I haven't sung many hymns lately. I'm not much acquainted with hymns." "Didn't your mother teach you any?" questioned Nellie's rather surprised voice. "My mother always used to sing hymns with us, when she was well." The young man did not answer. From the grounds where the fair was being held there came across to the lodging-house this afternoon stray shreds of the music played by bands. Such a fragment of melody wandered in now, but the young man did not heed it. What he seemed to hear was a mother's voice of long ago, singing to him, as once she sang: "Hush, my dear, lie still and slumber; That night when one of the employees of the fair came in to see how the sick man was, the visitor was requested to search in a trunk for some paper and a pencil. "Going to do some writing, Phil?" asked the young man, as he hunted for the required articles. "Yes," answered Phil, soberly, "I'm going to write to my mother." The visitor looked up, surprised. "I didn't know she was living," he said. "First time I ever knew you to write to her. Where does she live?" "In Ohio," replied the sick man, carefully beginning to sharpen his pencil. "I haven't written to her since I ran away to California, five years ago, when I was fifteen years old." His friend looked at the young man. "It isn't a bad plan to write to her," he ventured in a low tone. "No," returned Phil, gravely, "it isn't." Phil wrote laboriously at first. He tore up and threw away what he wrote. The employee, seeing that the task was likely to engage Phil's attention for the whole evening, pushed the lamp nearer, said, "Good-night," and went away. Phil continued to write. By and by a big tear ran down his check. He brushed his eyes, and caught his breath. He wrote faster. He folded the paper and put it into an envelope. He addressed the envelope, and then, as be looked at it, lying on the table, the lamplight showing plainly the dear home-name, another big tear ran down his cheek. "Mother!" he sobbed, "Oh, mother, I want you!" Not even the child-disciple who lay asleep in the next room knew what her words had been made use of to accomplish that night. Five years! How far, how very far from the Lord Jesus had Phil wandered in that time! And now would Phil listen to the voice of a child, calling him back to the Father's house? Chapter VIII. The postman went hurriedly up the steps of a house in an Ohio village. He rang the bell in a quick, decisive way, and thrust a letter under the front door. A woman whose hair was partly gray came into the hall, and picked up the letter. She found her glasses and looked at the writing on the envelope. Her hands began to tremble. She took the scissors and cut the edge of the envelope, her hands shaking so that she could hardly use them. She read a few words. "Oh, it's Phil! It's Phil! It's my boy!" she sobbed. "It's my boy at last! Father!" She ran out of the back door, calling her husband. He was a bent, white-haired man, who was cutting kindling in a shed. "Father! Father!" his wife cried. She rushed in, put the letter into his hand, and leaned sobbing on his shoulder, as he vainly tried to read without his glasses. "It's Phil! It's our boy! He's alive!" sobbed his wife. "He's sick in San Francisco! Oh, my boy! I want to see him!" "Phil!" exclaimed the father; and the old couple cried together. Five years! How many days the father and the mother had missed their boy! How many nights his mother had cried over never hearing from him, never knowing what had become of him! How many times the father and the mother had prayed for Phil! Oh, Phil must have known that what he said to Nellie could not be true, "I don't think my mother would care to see me." He might know that he deserved to be forgotten, but he must have hoped that his mother could not forget her boy, however wicked he might have been. "I want to see him," sobbed the mother now, as she leaned on her husband's shoulder. "You shall," answered the old man's choked voice. "We'll both go West and find our boy. Maybe the Lord's going to save him yet." Then they went into the house to read Phil's letter over and over, and laugh with joy, and cry again. The next day the neighbors knew that old Mr. and Mrs. Wadsworth had heard from their boy, who ran away five years ago, and they had telegraphed to him that they were coming to California, and they were going immediately, without waiting to make any preparations. Some of the neighbors hurried to help the old couple pack. But neither the neighbors nor old Mr. and Mrs. Wadsworth knew that the words of the little follower of Christ had been used to cause Philip to write home. The minister, Mr. Stanhope, was right, when he told Augustus and Nellie, "There never is a time in our lives so sad that we cannot look around us and find something to do for our dear Master." We may not always know how far the work we do reaches, but oh, if every one would give his or her life to Jesus, and would abide in him, taking his help to keep from sin, knowing that we can do nothing without our Savior, how much good little hands and hearts and lives might do! But all our working will amount to nothing, unless we first let Jesus into our own hearts. We must begin by belonging to Christ ourselves. No amount of "doing good" can ever take the place of really giving our hearts to Christ. It was because Philip knew Nellie really felt what she said and sang, that her words touched his heart. It was while Philip's father and mother were on their journey westward that a sad day came to Augustus and Nellie. That day the little lunch-counter at the fair was kept closed. People glanced at the counter as they wandered by. A few persons who had been advised to go to the place for lunch sought it, were disappointed, and went away to seek other lunch places. The old janitor and the keepers of several booths knew why the Denby lunch-counter was closed, but none of these people said anything about the reason to the new persons who came and looked and went away again. When lunch-time came, however, the old janitor wandered off by himself near the imitation Firth Wheel, which carried its loads of oranges and nuts around and around, and he said to himself sorrowfully, "Poor little folks!" And the man who made glass pens sighed to himself, "I don't believe I feel hungry this noon." Early that morning word had come from the hospital to Miss Ruth that she had better bring the children there as soon as possible. The message was from one of the doctors of the hospital, and Miss Ruth knew what it meant. Hastily she made ready, her heart aching for the children. She and they hurried away on the car. At the hospital they were met by one of the nurses, who took them into the ward where Mrs. Denby lay. Someone had put screens around the bed, so that the sick woman was somewhat shut off from the other patients of the ward. A doctor stood by the screens. He was a young man who studied with the older physicians in the hospital, and he was keeping watch of Mrs. Denby just now. "I am glad you brought them," he said softly to Miss Ruth, as he looked at Augustus and Nellie. The look was very kind and very pitiful. He took Nellie's hand and led her to the bedside. Mrs. Denby did not open her eyes or show any sign of recognizing the children. The doctor had turned aside, and he spoke to Miss Ruth in an undertone that the children did not overhear intelligibly. "We hoped she might stand the operation better. I thought I ought to send for you," he said; and then he added, with tears in his eyes, "I know how to feel for those children. My mother died when I was only a little fellow." They all quietly sat down and waited. Half an hour slipped away, and still Mrs. Denby did not stir, except with her light breathing. An hour went by. The doctor sent Nellie and Augustus outdoors into the sunshine. Miss Ruth remained with Mrs. Denby. All day Miss Ruth stayed by the bedside. No change seemed to come to the patient. Augustus and Nellie stepped softly in, from time to time, lingered with Miss Ruth and went out again. When night came, Miss Ruth took the children back once more to the lodging-house. The doctor had promised to send word of Mrs. Denby's condition, the next morning. Miss Ruth's heart was very tender as she kissed the children good-night that evening, for she thought, "They will probably be motherless in the morning." |

|||

|

|||

| Chapter IX. It was two weeks later when one night Miss Ruth came softly into her room at the lodging-house, and put her lamp on the stand beside the bed where Nellie lay asleep. Miss Ruth bent over the little girl. There was a tear yet lying on Nellie's flushed cheek, but Miss Ruth kissed the tear away. "Nellie!" she said softly, "Nellie! wake up, dear! I want to speak to you." There was a thrill of great joy in Miss Ruth's tone. The sleeping child stirred, and drowsily opened her eyes. "Nellie," repeated Miss Ruth softly, "I want to tell you something about mamma." The little girl started up. "Oh, Miss Ruth!" she cried, trembling. But Miss Ruth's arms held the little girl tightly. "No, dear," said Miss Ruth soothingly, "it isn't that. It's good news I've come to tell you. That kind doctor has just been here to tell us. He said he couldn't wait another hour to let us know! Nellie, the doctors say that they do believe, if your mamma keeps on without any relapse, she will get well! They are very hopeful of her. Why, Nellie, child!" Even Miss Ruth was not prepared for the storm of weeping that followed. "Have you told 'Gustus?" faltered Nellie when she could speak. "Yes, I've told him," answered Miss Ruth. "The doctor made me promise to wake you both and tell you to-night. I expect that a month or two from now, there'll be as great an uproar here over your mamma's coming back as there was over young Mr. Wadsworth's father's and mother's coming, the other day. Our landlady will begin to think she has an exciting company of roomers, I'm afraid." Nellie hugged Miss Ruth. It seemed the only way in which she could express her happiness. "Now go to sleep," advised Miss Ruth, kissing the little girl. As Nellie laid her head again upon the pillow, she remembered what Mr. Stanhope had said, that sad time when her mother was to be carried to the hospital: "Perhaps God is going to give you just what you asked for - a well mother again - but you must let him give her to you in his own way. We should never tell God how he must give us a thing." "He did it the best way," thought the little girl thankfully, now. Ah, how jubilant were the days that followed! The work now seemed as nothing. Their mother was coming back sometime! Nellie sang, and Augustus and she and Miss Ruth had gleeful countings of earnings. Nellie could not do enough. Then came the day when the children were first allowed to go to the hospital to see their mother, pale and thin still, but with a smile on her face, and her arms outstretched to gather Augustus and Nellie to her heart, crying, "My darlings! My darlings!" "Oh, mamma, mamma!" exclaimed Nellie, "you're really going to get well, aren't you?" And then the mother and the children clung to one another, and Mrs. Denby cried, and they kissed one another, and laughed, and cried, till the young doctor, who was standing by, found tears in his own eyes. The children explained to their mother how well Miss Ruth and they were managing, and then Augustus had a chance to tell his mother about the things he had seen at the fair, and Nellie told what she had seen. Mrs. Denby was quite weak, still, but she smiled and enjoyed the talk. The young doctor and the nurse sent the children home before long, but they had the promise of seeing their mother again very soon, for Mrs. Denby declared for herself that the sight of Augustus and Nellie did her more good than any medicine. After that, the weeks seemed to fly, there was so much to be done. "Do you suppose we shall have enough money for the mortgage?" the children eagerly asked Miss Ruth every day. That was the exciting question that animated not only the children and Miss Ruth, but divers other people who had set their hearts on the same thing. Surprising was the number of people who were recommended by somebody to take lunch at the Denby counter, and Nellie and Augustus could not disguise their satisfaction, as they hurried by one another to wait on customers. And if certain persons gave Miss Ruth a little money toward the mortgage, and if Philip's father helped a little in that direction, too, it was no more than they were glad to do, though the children knew nothing of such aid, but went on rejoicing in the work they could do toward lifting the debt. At last a wonderful day came - a day when Miss Ruth sent the minister, Mr. Stanhope, one hundred dollars, with instructions to pay Mrs. Denby's mortgage! That day it seemed to Augustus and Nellie that they were the happiest persons at the fair. But they were really happier when they went, the next Saturday, to the hospital, and, full of excitement, told their mother the good news. The weeks flew along till at last the great fair was over. The electric lights, and the fireworks, and the music, and the Firth Wheel, and the Colorado gold mine, and the Eskimo village, and the Turks, and Arabs, and Cingalese, and the people of Damascus, and the South Sea Islanders, and the ostriches, were all memories to many people. Philip's father and mother had taken their boy to the old Ohio home again, to begin a new life there, by the help of God. And one day Miss Ruth, and Mrs. Denby, and Augustus, and Nellie, sat on the deck of a steamboat and looked back at the city that had held for them so much anxiety and work and hope, during the months of the fair. "Do you wish you had to live the fair all over again, Nellie?" asked Miss Ruth, smiling and looking at the face nestled close to Mrs. Denby. Nellie smiled, but shook her head. "No," she answered, "I'm glad we're going home. But maybe mamma never would have got well if we hadn't come down here to the city doctors, and maybe we couldn't have got the money for the mortgage if we hadn't come." Mrs. Denby looked down at the childish heads beside her, and thought of the words: "He led them forth by the right way, that they might go to a city of habitation." Some such thought must have been in Augustus' mind, too, for as he looked back at the city across the waters of the bay, he said, softly, "God made everything come right after all, didn't he, mamma?" And Mrs. Denby answered, "It would have been right, whichever way he led us, dear, but I am thankful he permitted us to be all together again." Gradually the outlines of the city faded away in the fog, and the little company sailed on, safe and happy in the care of the Father who had kept them thus far and who would watch over them all the rest of their lives. |

|||

|

|||

|

|

|||